AARP Hearing Center

Editors note: Dr. Stu Ervay is a member of the AARP Kansas Executive Council and a volunteer for AARP Kansas. In this blog, he shares his experiences as the husband of his wife of 58 years who has been diagnosed with Alzheimer's.

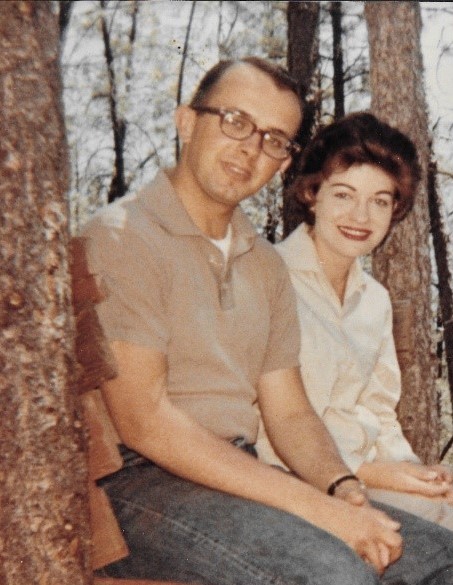

In March of 1962 I had a third date with a college senior. While third dates are not uncommon, our dates involved my driving five hours from central Texas to near the Oklahoma border. I must have been captivated by this young woman because my military obligations were demanding, and time off was precious.

But on that third date I began to wonder if I was being smart about this budding relationship.

She revealed a side of herself I wasn’t sure how to handle. Over a restaurant dinner she told me how much she loved to dance.

Me? I could take it or leave it.

But she enjoyed it so much that every noon hour she and her friends would dance to the jukebox at the student union. Interesting.

Then she started talking about some of the young men who participated in that version of what sounded like an early afternoon tea dance. Since I stayed overnight in a men’s dorm during my weekend visits, I had met two or three of them. Seemed like nice guys.

As my date and I conversed more, I learned that at least one of them was homosexual. And she had become his confidant and friend. She made it clear that her own preferences as a woman were not in any way similar. But she cared for this gentle pre-ministerial major who was suffering psychologically, spiritually, and emotionally. It was 1962, after all, and attitudes then were quite different than today.

I listened.

Given the era, I wasn’t sure what to think about this young woman who was willing to counsel a man who, in my military unit, would be cashiered out as soon as possible. My church called his condition a sin. In polite society he would have been considered a pariah, and for him to even consider the ministry was ludicrous.

The woman I was dating lived in a dormitory full of female students who couldn’t understand why she would befriend a man like that. And I, too, had a difficult time coming to grips with it.

I left that weekend making no plans to return, saying something noncommittal about staying in touch. She thought that was understandable and made no effort to encourage my return.

The drive back seemed much longer than five hours. I was conflicted. By the time I drove into the post I was emotionally exhausted. The subsequent days and weeks were filled with difficult and even dangerous military maneuvers and exercises. I was almost grateful for them.

This situation with the young woman wasn’t something I wanted to discuss with my fellow officers. I’m almost certain they would have told me to walk away saying something like “there are other fish in the sea.” So, I felt alone as I mulled over the issues involved. And, in my aloneness, I had a few revelations.

What kind of woman was I dating? No doubt, she met my father’s description of someone with substance and conviction. And her convictions were scripturally based if the guy was in fact a sinner.

How alone that guy must feel, especially if his sin is something he can’t help because of biological and psychological wiring. How alone my young woman must feel when risking the friendship of both male and female students on campus.

I sensed she liked me. So, what courage it took to share with me a story that was so counterculture.

Was she testing me? Maybe. Could I have her kind of courage? I didn’t think so.

But slowly my admiration of her grew. Many women I dated up to that point were self-absorbed and superficially judgmental of others. I couldn’t think of even one who would reach out to someone in need, much less risk the bad opinion of their peers. They sought social acceptance, often through membership in a college sorority. My young woman wasn’t interested in that kind of thing.

I sensed she wanted my love, but only if she could be an authentic Christian servant to those shunned or held at arm’s length. Our discussions about what she wished to accomplish in education brought out those points very clearly.

She risked the possibility of being alone the rest of her life if her prospective mate couldn’t accept who and what she was as a caring woman. As a human being who both wanted and needed meaning in her life.

One night I wrote her a long letter. Apologies. You know, intense military training and all that. I asked for another weekend date. She wrote back, telling me there was no need for an apology and that she’d be pleased to see me again.

A few months later we were married. And for nearly 58 years she has reached out to others less fortunate or shunned by others. Her students. People in the churches to which we belonged. Others who needed to know they aren’t alone and rejected.

A life well lived! Even now in the fog of Alzheimer’s.

-----------------

Aloneness is much different than feeling lonely. That young college senior I dated over 58 years ago taught me much about the importance of holding well-reasoned and valid convictions in the face of possible rejection.

No, it hasn’t been an Ayn Rand story like The Fountainhead, in which the hero remains an individual true to his own talents in the face of overwhelming rejection. It is instead the acceptance of the Christian credo that we stand by the “least of these” no matter what. No matter how much we are disdained, shunned, or criticized for breaking any social standard now in vogue.

Aloneness is often the result of living or working outside the lines of social expectation. It was more palatable when “I” was part of a “we.” Pillow talk. Coffee in the morning. Solace in the face of what could seem like insurmountable odds.

Old habits are hard to break even when the “we” is absorbed by Alzheimer’s. Aloneness is more agonizing than ordinary loneliness. In the next few blog posts, I’ll explain why.

What are your thoughts about aloneness? In the meantime, seek ways to take care of yourself.

©2020 Stu Ervay - All Rights Reserved

Stu is a retired university professor and consultant to public schools. Prior to his work in higher education, he served as a unit commander in the United States Army, and taught history and government in secondary schools. Since retirement he has written journal articles and a book on school improvement. He is now a state AARP volunteer leader. His wife, Barbara, is also a retired educator. In addition to many years of teaching middle school science, she played a significant role as an advocate for women in church leadership.