AARP Hearing Center

Algona historian Jerry Yocum still remembers the day he learned about the town’s critical role in World War II. Just a little boy then living in nearby Pocahontas, he had no clue that telling the story of Algona’s unusual contribution would later become – and remain - his retirement passion.

Algona served as a base camp for more than 10,000 German war prisoners over 2 ½ years, part of a national strategy to provide farm and food laborers while millions of U.S. soldiers fought overseas. One day Jerry’s father, who owned a school bus, was hired to transport prisoners for farm cleanup duty after a tornado. Dad brought his son along.

“That seemed like the end of the story, “ Jerry says.

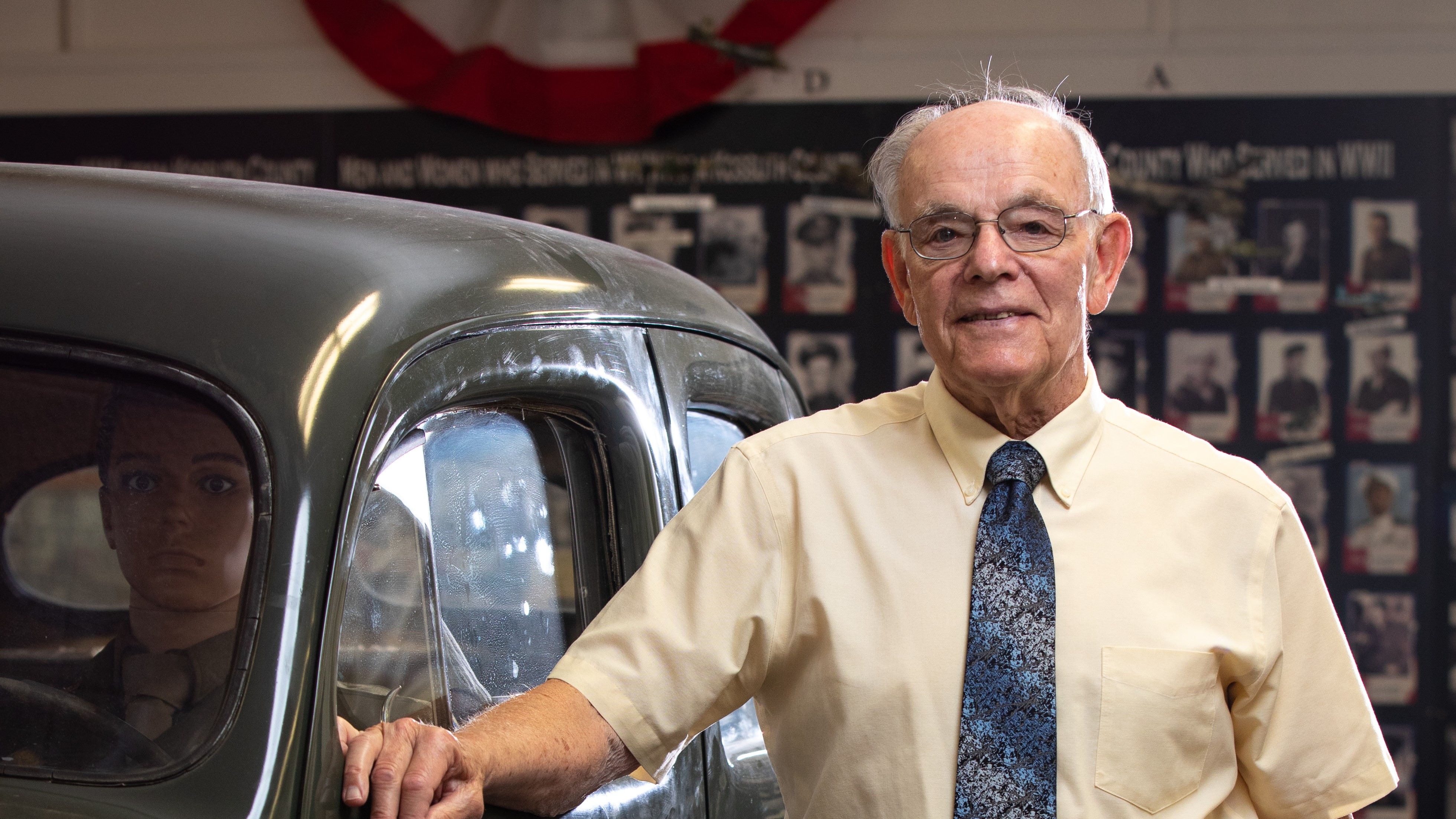

But his brush with the Algona prisoner camp turned out to be just the start of his story. Things came full circle decades later when this 83-year-old retired history teacher helped bring the camp’s story to life again via a new museum.

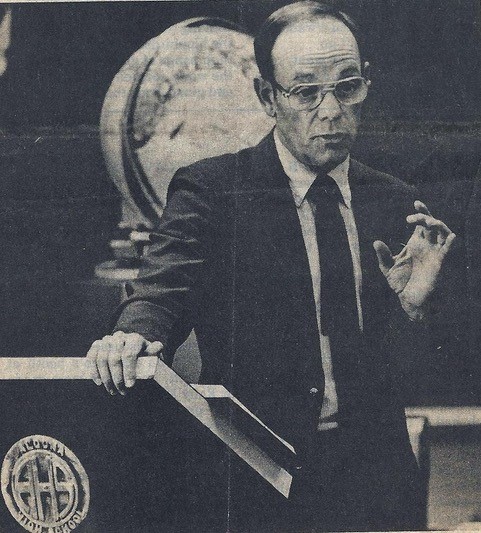

Jerry’s career as history teacher and coach led him back to Algona in 1969 to teach at the high school, a post he’d keep until his 1996 retirement. Around that same time the idea of a museum to showcase Algona’s special war story was taking shape and Jerry signed on, joining the inaugural planning committee in 2001.

Three years later and about 60 years after that one bus ride with the prisoners, he helped open the doors to the new museum. Today, he serves as board president and arguably remains the museum’s most public face.

Edna, his wife of 63 years, likes to tell him, “When you retired and left the classroom, you got another one.” This one just happens to be in a museum.

Much too young to enlist in WW II, Jerry still grew up surrounded by the war and its impact. He remembers following news reports, discussing current events over dinner, and learning that for him the term “war rationing” meant a longer wait for a new bike. He practiced blackout drills and recalls his high school sister’s classmates stopping by the house in fresh military uniforms to say goodbyes.

It all helped spark a lifelong interest in history, especially about the war. And by middle and high school years, after meeting a few particularly inspiring teachers, Jerry had made his decision. “I wanted to be like them,” he remembers, teaching history and coaching sports.

Meeting Jerry quickly dispels any stereotype about boring history teachers. A runner-up Iowa Teacher of the Year, he earned a reputation for bringing history to life in the classroom. Simulations and role-playing helped drive home important chapters like farming challenges in the late 1800s or the movement to give U.S. women the vote. When one class studied President John F. Kennedy’s assassination and related controversy over the “lone gunman,” Jerry had a colleague step into the room and fire a starter pistol, as Jerry dropped to the floor. The rather unusual act and discussion to follow vividly showed that what witnesses thought they heard or saw could often differ from the facts.

Long-time friend Ro Foege, who first met him as a third-grader, says qualities that drew him to young Jerry are the same ones people have admired through the years. “He was one of those people that just reached out to others,” said the former state legislator, now living in Cedar Rapids.

Jerry credits his parents for instilling in him the importance of being involved, not just politically but in being a good citizen and giving back to the community. He tried to teach a similar message to students. “They all have a role in our society,” he says.

Given Jerry’s dual interests in history and giving back, the museum project was a natural. The town already had a strong reminder of its war role thanks to a 65-piece nativity scene built by German prisoners, who paid for all the supplies with their prison wages. When war ended, the massive nativity was left to the town that displayed it annually from 1945 on. Information discovered by the nativity project volunteers even helped jump-start the museum team’s efforts.

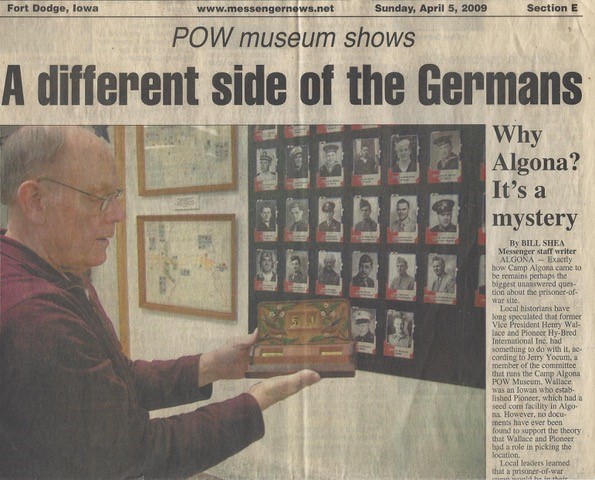

Still, starting a museum from scratch presented challenges. “This was the most important thing that happened to our community in World War II,” explains Jerry, and it needed to strike the right tone. Yes, it was a prison camp with guard towers, but prisoners weren’t beaten and ate quite well, in sharp contrast to treatment received by some U.S. prisoners abroad.

The 287-acre camp actually gave a welcomed boost to Algona’s wartime economy. The compound regularly housed more than 2,000 men, and it also served as lead camp for 34 smaller branches scattered in four states. The national network of camps, with more than 400,000 German prisoners in all, performed jobs ranging from tending crops to canning food, from cutting and milling lumber to processing chickens.

Why Algona? The mystery remains why the town was chosen as a lead POW camp. Some speculate it had to do with its proximity to a four-state area.

Jerry has always pondered the irony of the prisoners’ role: “In many ways, what the prisoners did was raise the food that not only helped feed themselves but fed our allies. Somewhat unwittingly, they were helping us win the war.”

At first, the museum’s exhibits only needed one wall. Today, the building is brimming with glimpses of the Algona prison’s past while capitalizing on modern offerings like touchscreens and a visitor welcome video. A rich collection of memorabilia includes old prisoner bunks and examples of prisoner artwork. A separate wall also shares the story of Kossuth County’s own veterans, including local soldiers imprisoned by the Axis side under much harsher conditions. Their story became a book - with Jerry as lead writer - called “13,000 Nights: Kossuth County Men in Axis POW Camps in WWII.”

After two decades, Jerry still gets excited talking about his museum work. “You never know for sure what’s going to walk through that door” and it could be another story to enrich the museum, he explains.

In this case, once a history teacher, always a history teacher.

Explore the Camp Algona POW Museum website.

Next Month:

Our August Hidden Gem vividly remembers entering her first powerlifting meet in late 2018. “I was terrified,” she says. But this 56-year-old Oxford mother of nine and grandmother of nine powered through those butterflies. Today, she’s still passionate about improving, competing and setting deadlift records for her age and weight class.