AARP Hearing Center

Mary Young Bear’s days are steeped in her rich Meskwaki heritage. She lives it from her home on the Meskwaki Settlement near Tama. She works it as conservator and cultural director of the tribal museum there. But she also enriches it through her creations of intricate beadwork and regalia.

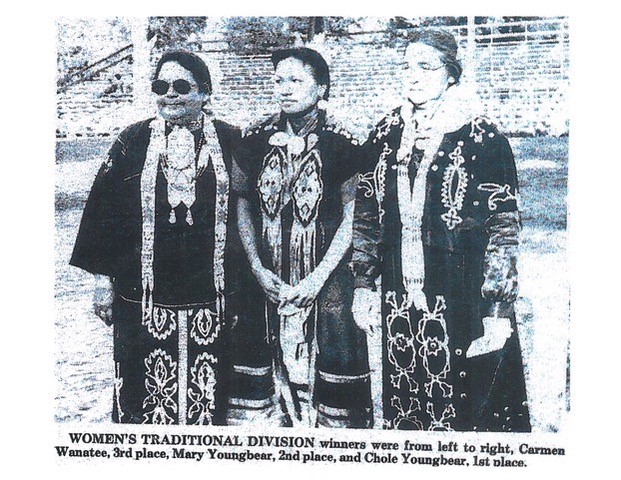

Mary basically taught herself to bead beginning at age 8. Her reasons then were pretty kid-centric: She wanted regalia to wear to the intertribal dances she and her family attended near their Denver, Colo., home. She’d watched her beloved grandmother, her Kokomas, constantly beading. So after a few lessons from Koko, Mary started experimenting and never stopped.

And yet when her father George proudly said her bead talent would be something she could do the rest of her life, she was not amused. Was this really the best she could achieve, she recalls wondering, noting, “I just didn’t respect my work at the time.”

Her father’s prediction proved right and Mary, 61, deserves all the respect she’s earned for her bead artistry. Her talent continued growing right along with her deepening Meskwaki pride. Now, her knowledge of textiles and beading is so extensive she can pretty accurately date a piece of fabric and its beads just by looking at it.

The Meskwaki, which translates to People of the Red Earth, boast a rare history among Native Americans. Its people have never lived on a federally owned reservation in Iowa. Though the federal government tried to force them onto a Kansas reservation in the mid-1800s, some simply refused to leave. In 1856, the Iowa Legislature amended state law to officially allow them to remain in Iowa, and the next year the Meskwaki Nation bought its first 80 acres of woodland along the Iowa River. With that initial investment, the Meskwaki persevered and expanded to own more than 8,100 acres now in three counties and includes a successful casino and bingo hall as well as a growing array of non-casino businesses.

Mary traces her ancestors back to those earliest Iowa days. Her Meskwaki name, Bo na bi ga, “is the most important name we have. We borrow these names,” she says, noting hers belonged to her great grandmother.

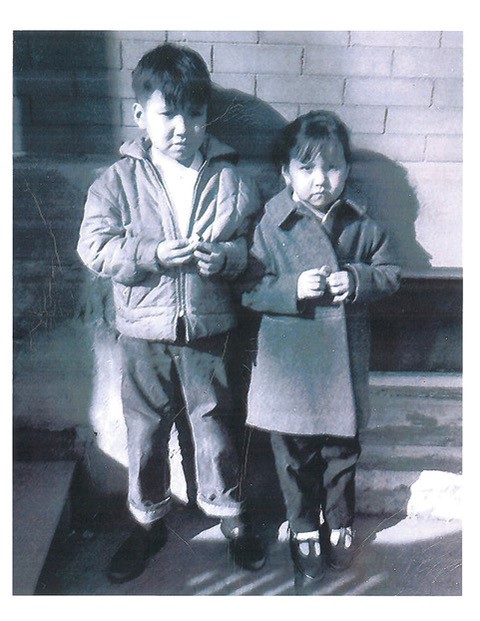

Though her roots are deep in Iowa, Mary was born in Denver. The federal Indian Relocation Act of 1956 offered incentives to lure Native Americans into major cities. Mary’s grandmother made the decision first to relocate her family, hoping for better job opportunities. When Mary’s father also moved from the Tama settlement, her parents married and together had six children.

Mary carries wonderful memories of her Denver days. “There was a community of Native Americans that were deeply supportive of each other,” she recalls. But at age 19, her life changed sharply when her father decided to return to the settlement. Her parents had parted by then, and her father asked Mary to move with him to help raise two younger sisters. Today, she cannot imagine living anywhere but the settlement, yet then she was torn about moving to a place she’d only visited with family. Still, she agreed and soon found the family squeezed into her grandfather’s two-room house with no indoor plumbing, no running water, and all cooking done outdoors. “It was an adventure,” she remembers now, with a smile.

It was important that that aspect of my work would be passed down to the next generations, and to make our own young people see how relevant that is, not to just go borrow from other tribes’ styles.

In time, the tribal council built her father a more modern home. But about five months after they moved in, George suffered a fatal heart attack. Mary was now responsible for her sisters while also starting her own family. She eventually had five children of her own, though she never chose to marry. “I think I’ve been independent for so long,” she says, “I don’t think I could do anything else.”

Through all these life passages, beading has been her constant. “I guess it was a passion. It still is,” she says.

Her preferred beading surface uses a canvas backing coated with an acrylic gesso primer, which keeps her creations durable yet flexible for ceremonial pieces. Her earlier designs were more contemporary, but in the past 15 years, they’ve focused on her heritage. Her regalia features representations of the Meskwaki environment: flowers, trees, vines, animals, and animal prints. Colors often honor a specific clan.

Some somber reflections drove this conscious shift in design style. Several relatives already had died rather young, and in case that was to happen to her, Mary first wanted to learn more about her grandmother’s beading and about the unique Meskwaki style. “It was important that that aspect of my work would be passed down to the next generations, and to make our own young people see how relevant that is, not to just go borrow from other tribes’ styles,” she says.

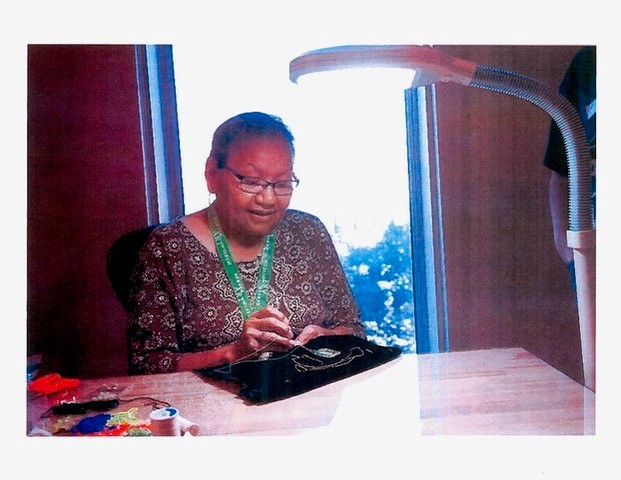

Her cultural refocus, coupled with her Denver roots, attracted the attention of the Denver Art Museum, which offered her a two-week artist-in-residency in 2016.

Mary’s never tracked how many regalia designs her hands have beaded over the years. Most were made for her family to wear for ceremonial occasions. One beloved piece has been worn by all her daughters and now by one of her ten grandchildren.

But eldest daughter Nyla Lasley notes that her mother also creates regalia for families throughout the settlement, “most of it without any expectation of compensation.” Mary sometimes designs regalia, too, for other children on the settlement who otherwise might go without. “It is a way for me to give thanks to the creator for giving me this skill,” she says.

Her impact within the Meskwaki Nation reaches beyond her art. She’s held leadership roles, including school board president, and Nyla proudly notes her mother’s generosity. “She’s always donating and supporting and helping. I don’t how many fundraisers she’s done and how much money she’s raised for all these organizations, for all these people,” she says. Mary says simply: “I just go where I’m needed.”

She’s particularly passionate about mentoring youth and being an ambassador for Meskwaki culture with outside communities and groups. Her lifetime contributions were recognized last year with induction to the Iowa Women’s Hall of Fame. The Meskwaki Nation’s Facebook announcement of her selection triggered an outpouring of congratulation posts. “We need more strong, beautiful, caring Native American women leaders like you,” wrote one commenter.

The scope of her cultural museum work narrowed this past year thanks to COVID. The building remains closed to the public, and workshops and classes she once led are on hold. Yet from her corner office, with its wide file drawers of art samples and treasured relics, she’s still at work cataloging. In her nine years at the museum, she’s helped curate the largest collection of Meskwaki cultural objects in the world.

This now-senior tribal member has great hopes for the next generation. Meskwaki settlement schools teach the native language and culture, and that, in turn, helps young people appreciate the value of retaining tribal lifestyles and beliefs. “Kids are kids, they want to do other things and watch TV or go to movies,” she says. “But still that core, that intangible part of being a Meskwaki, is right there.”

And she’s delighted another Young Bear carries on her love of bead artistry. All her children learned to bead and often help complete short-notice projects. But she thinks her youngest son Daniel, 31, “is an exceptional artist. I would put him above where I’m at.”

Her motherly pride is tangible. In fact, ask which life achievement makes her proudest, and she’ll answer: “My kids and just the fact that they’re pretty well-grounded. They know this is their home, these are our people and these ways are important.”

For this distinctive artist who lives to honor her Meskwaki ancestry, that’s what matters most.

Photos courtesy of Mary Young Bear