AARP Hearing Center

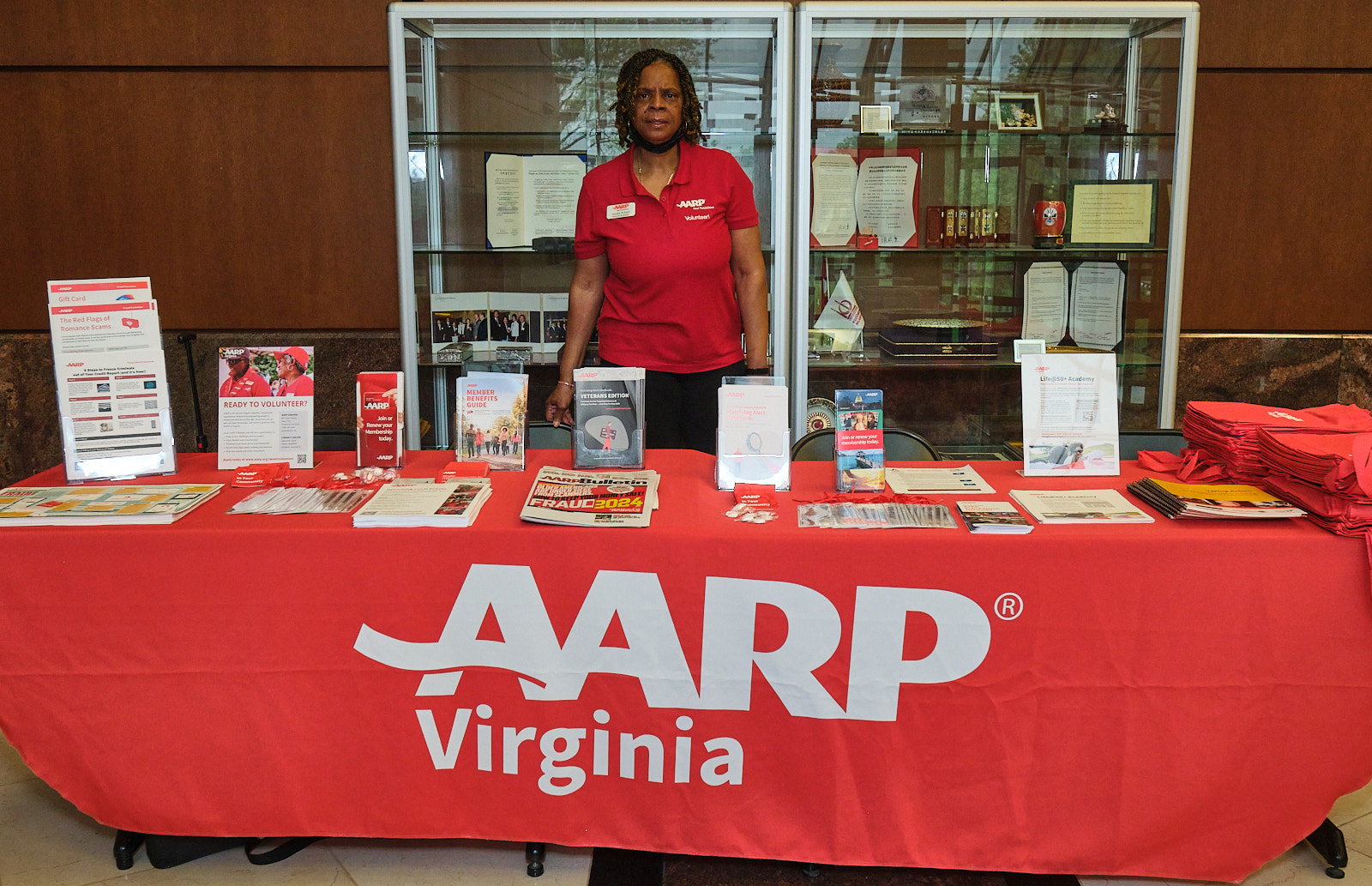

The 7th Annual Fairfax County Scam Jam focused on Artificial Intelligence (AI), used with increased frequency in scam entrapment schemes. The Scam Jam is a joint venture by AARP Virginia and the Fairfax County Silver Shield Task Force.

Keynote speaker Dr. Stephen Ruth of George Mason University discussed both the pros and cons of AI. Ruth defined AI as a set of technologies that lets computers perform a variety of tasks, emulating human language and behavior without human interaction.

Some of the more benign examples include man vs. computer chess games, motorized vacuums, and the incident where IBM’s Watson computer beat Jeopardy! champion Ken Jennings.

Ruth explained that AI works by “scraping” the internet for information, and anything found online is scrapable. This aids in the development of synthetic profiles that can provide misinformation.

The danger, said Ruth, is when tech growth becomes unattainable. At a recent global conference, technology experts expressed concerns that AI poses a “risk of extinction on par with nuclear war” because of the rise of misinformation due to AI involvement in scams.

AI does have plenty of positive applications, emphasized Ruth, especially in fields such as medicine and agriculture. “Cobots” are systems that work alongside doctors for surgical applications, and AI programming helps farmers with planting and irrigation.

A common real-world AI application is ChatGPT, a chatbox developed by OpenAI designed to provide a safe and beneficial AI experience. By using “prompts,” a user can ask ChatGPT to write a poem or story, recommend a restaurant, or test their knowledge. Politicians can send notes to voters based on the voters’ profiles. The outcome is as specific as the prompt.

AI applications designed to be helpful can sometimes go too far, said Ruth. While AI helps with car repairs, it can also be a gateway to hacking into a car’s computer system, allowing a manufacturer to potentially shut down the car.

Ruth said AI can potentially have a “profound effect on climate change, but governments need to have a place in implementing it.” He cited Rep. Don Beyer (VA-8), who is taking AI classes at George Mason, as an example of government officials seeking to use their power and knowledge to influence legislation.

Financial fraud has “skyrocketed since COVID,” said Jim Hitchcock, vice president of fraud mitigation for the American Bankers Association. He advises diligent monitoring of accounts using the acronym CAR, for challenge, authenticate, and report.

Check fraud continues to be a significant issue because criminals are now able to alter checks by “washing” them to erase the payee and dollar amount. These washed checks are then digitally copied and deposited remotely.

Although check usage has declined as a whole, older adults are the demographic most likely to still use checks. Hitchcock recommends using gel ink pens when checks are necessary, as they are more likely to prevent criminals from washing checks, but the best defense is to monitor accounts online regularly.

If a check doesn’t clear or there is any unusual activity on an account, contact the bank as soon as possible, as the sooner the bank knows about an issue, the more likely the bank may be able to recover the funds.

Wire or ACH (Automatic Clearing House) transfers are more difficult to recoup, said Hitchcock, but again the bank needs to be notified as soon as possible. If a transfer goes out of one account, the bank may be able to work with the receiving bank to slow down the process as they investigate the claim.

Banks and credit card companies typically monitor accounts and notify customers if they see uncommon activity. Monitoring is still key, said Hitchcock, because scammers use emails, text messages, and phone calls claiming they are banks requesting information.

Hitchcock advises diligence if anything looks unusual. Instead of responding to such messages, call the bank directly and ask to speak to the fraud department.

Hitchcock also recommends regular password updates and use of multi-factor authentication on logins, although he acknowledged that fraudsters could find their way around almost any defense. Monitoring accounts is the best defense, he said.

The American Bankers Association has a helpful online quiz called Banks Never Ask That which helps users understand bank-related scams, said Hitchcock.

“Financial fraud is so out of control,” said Kevin Gallagher, FBI supervisory special agent. Gallagher says education is the best weapon to fight it.

Most of the fraud the FBI has investigated to date hasn’t involved AI, but it is concerned for the future, said Gallagher. Investigations into call centers in Southeast Asia and China have uncovered information that says, “no one is unscammable – you just need the right script,” he said.

The FBI is particularly concerned about the use of AI in elections. AI can create synthetic entities by copying voice and facial characteristics, as well as hacking social media accounts, to spread misinformation. These “deep fake” accounts can trick the public into believing false information.

“Always check the source of information,” said Gallaher. Did it come from a respected news source, or was it on social media or a biased website?

Deep fakes of celebrity likenesses have been around for a few years, typically replacing faces in videos with celebrity images. Recent fake nude photos purporting to be of singer Taylor Swift is an example of this practice.

Fake celebrity investment scams use a celebrity’s likeness and voice to gain victims’ trust. These scams often involve cryptocurrency.

Gallagher urges caution on answering phone calls from unknown sources. He especially cautions against identifying oneself and answering yes or no questions.

“It takes just 3.7 seconds for Microsoft AI to capture a voice,” said Gallagher. The voice can be cloned and used in scams of vulnerable people.

Gallagher recommends taking a hard look at how much one is available and open to others on the internet, especially on social media. Scammers exploit social media platforms to develop fraudulent profiles that can be used for fraud.

The FBI’s Internet Crime Complaint Center provides educational tools about online scams and a means to report fraud.

Even though she has worked in consumer protection, AARP Virginia Community Ambassador Jane King nevertheless found herself reeled in by the popular grandparent scam.

During the early years of the COVID pandemic when she was living in isolation, King received a phone call from a man claiming to be an attorney acting on behalf of her granddaughter Katie, whom he said had was being held by the Arlington County Sheriff’s office following a car accident.

King, who has a close relationship with her granddaughter, believed the story could be credible, especially after she heard Katie’s voice in the background saying, “I am so sorry, Grandma.”

The man instilled a sense of urgency, telling King not to call her daughter, Katie’s mother. To keep Katie out of jail, King was instructed to withdraw $15,000 from her bank account, and if the bank asked why, she was to say it was for home repairs.

In retrospect, King realized this was “very wrong headed,” but the scammer took advantage of her emotions, and she said her “concern for her granddaughter overruled common sense.”

She withdrew the funds, and they were picked up by an individual that the man said was a bonds man. When the man called back to demand another $15,000 for the pregnant woman Katie supposedly hit, King’s “rational brain function” kicked in.

She told the bank manager what happened, called her daughter, and reported the crime to the Federal Trade Commission. Katie, of course, was fine. Unfortunately, King was not able to recover the $15,000.

King’s experience is typical of this type of scam. The scammers likely had information about her relationship with Katie from online sources and had copied and cloned Katie’s voice. They also knew King had a substantial amount of money in her bank account. They played on her emotions and urged quick actions.

AARP Virginia volunteer Trudy Marotta, who served as the program’s master of ceremonies, closed out the event by providing information about AARP’s Fraud Watch Network, which has a wealth of information about scams and frauds, including what to do if you are a victim.

Following the Scam Jam, a shred truck collected 7,700 pounds of material from attendees.

The 2024 Fairfax Scam Jam video is available on Fairfax County’s government information website.