AARP Hearing Center

For married women during the Victorian era, it was a double tragedy if their husband died.

Not only did widows lose a spouse but they also faced up to two or more years of mourning, when they could wear only drab garments and mostly had to refrain from enjoyable activities.

Ashleigh Meyer, the director of historical research for the Old City Cemetery Museums & Arboretum in Lynchburg, discussed 19th century mourning customs during a recent webinar sponsored by AARP Virginia. At the webinar, Meyer invited the public to join her on Aug. 10 for a guided tour of the cemetery grounds and facilities.

Meyer explained the “prescriptions for mourning” during the Victorian era, roughly from 1820 to 1914 (largely during the reign of the United Kingdom’s Queen Victoria), when most of the burials at Old City Cemetery took place.

For a married woman, Meyer said, the first stage was called “heavy mourning,” which lasted a year and a day and required wearing a black dress and a veil – the proverbial “widow’s weeds” – at all times.

Then came “second mourning,” which lasted six to nine months, during which the widow could put away her veil and put on some jewelry.

Finally, Meyer said, there was “half mourning,” which lasted three to six months. During half mourning, the widow could wear muted colors other than black – dark green was a popular option. “But we're not going out in the town with our stilettos and our bright red dress,” Meyer said.

“After that period, you were finally able to move on with your life.”

Men had mourning customs, too. “But as in many other things, they get off pretty easy,” Meyer said. “Men mourned for about three to six months total, and they were allowed to go back to work.”

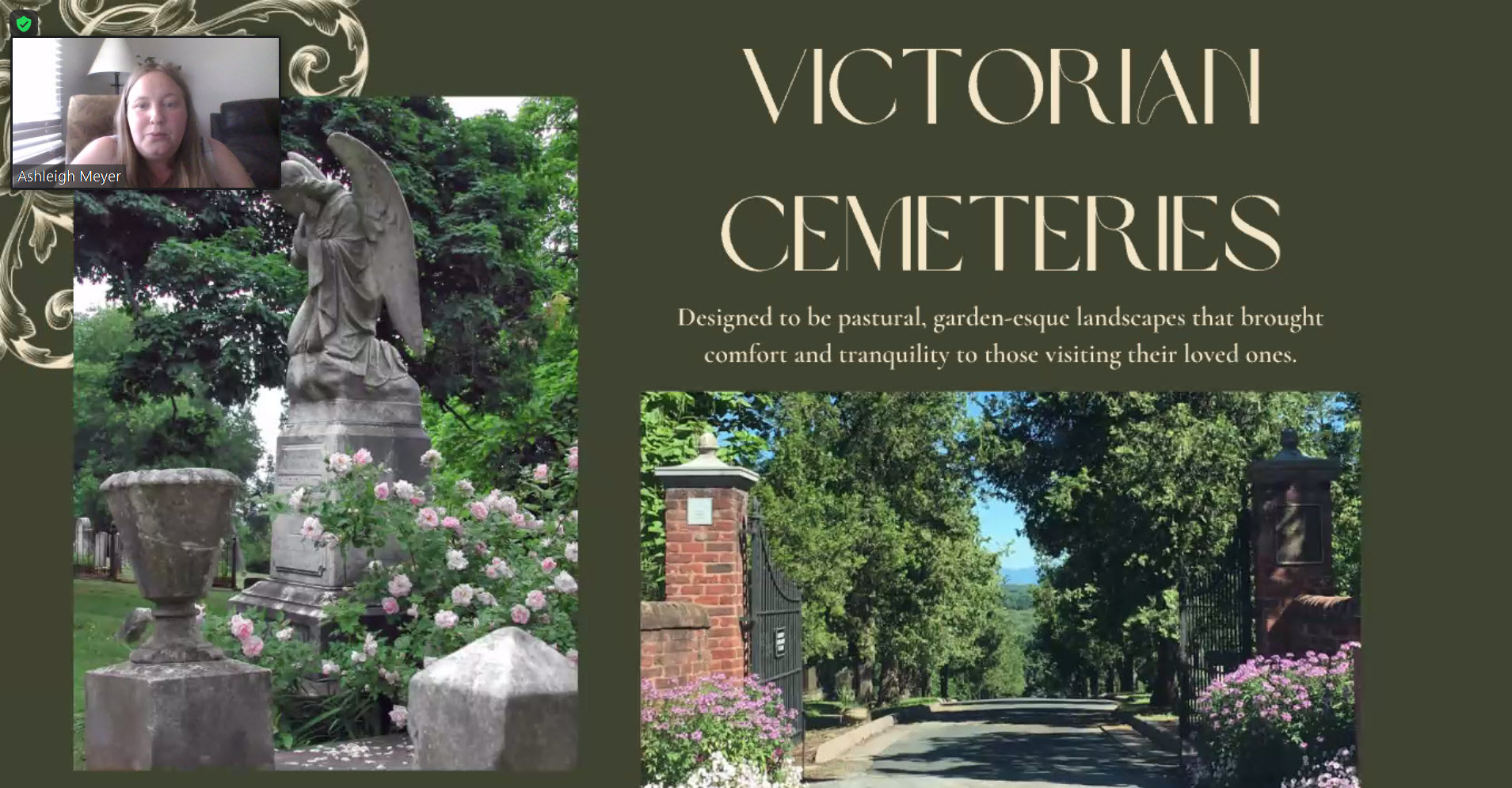

Old City Cemetery, which is on the National Register of Historic Places, has been the site of much mourning since its founding in 1806. It is the oldest municipal cemetery in Virginia still in use today.

Owned by the city of Lynchburg and managed by the nonprofit Southern Memorial Association, the cemetery features a 27-acre public garden and a “history park” with five museums.

Located in downtown Lynchburg, it is not only an active place of burial and remembrance but also a wedding venue – and the city’s most visited historic site, attracting more than 33,000 visitors annually.

Nearly 20,000 bodies have been buried in the cemetery. It is the final resting place for a broad cross-section of Lynchburg society – from the city’s “founding fathers and mothers” to paupers whose remains were interred in the Potter’s Field.

The cemetery holds the graves of Revolutionary War soldiers, Confederate soldiers (more than 2,200 from 14 states) and more than 13,000 African Americans, both enslaved and free.

Relatives of George Washington are buried there. So are the grandparents of Marian Anderson, the African American singer who broke down racial barriers.

The people interred in the cemetery reflected the harsh times centuries ago: “the town drunk,” a brothel owner, a teenager smothered by sawdust in a factory accident, a man killed during a battle between miners and state officials in West Virginia. A prostitute committed suicide by jumping into a canal; her body was later disinterred and used for dissection classes at the University of Virginia.

There also were local celebrities such as Blind Billy, an enslaved man whose musical talents prompted townsfolk to purchase his freedom; Josiah Holbrook, a founder of the “lyceum movement,” a 19th-century effort to educate American adults through lectures, debates and other public events (he died falling from a cliff while collecting rocks in 1854); and Wesley Wright, who patented the recipe for Bull Durham tobacco (with tonka beans and rum).

But the cemetery is more than just burial grounds. The site includes a pollinator garden, a lotus pond, a butterfly garden, a shrub garden, beehives, goats and hundreds of varieties of native and heirloom plants, with the largest public collection of antique roses in Virginia.

Old City Cemetery also includes five “house” museums:

- The Chapel and Columbarium honoring religious leaders buried there since 1806.

- A museum documenting medical practices during the Civil War era. It is in what was once Lynchburg’s “House of Pestilence” – the city’s first hospital, where people infected with smallpox and other contagious diseases were quarantined.

- The Hearse House and Caretakers’ Museum. It contains a turn-of-the-century hearse owned by Diuguid Funeral Home, the second oldest undertaking establishment in Virginia.

- A train depot that served as the C&O Railway Station in Amherst County from 1898 to 1937.

- The Victorian Mourning Museum, with exhibits on mourning attire and jewelry, the evolution of coffins and embalming, and funeral and mourning etiquette.

In the Victorian era, death was more common and more intimate than it is today, Meyer said. “People did not live as long, and children often did not survive to their teen years,” she said.

At least a third of the people buried in the cemetery are children under age 8. “That's just an unfortunate reality of the times,” Meyer said. “There were no antibiotics, no vaccinations. … As children, you were very susceptible to illness.”

Moreover, instead of at a hospital, people typically died at home, where their bodies remained for several days while relatives and friends came to pay their respects.

Until the Civil War, embalming was not a common practice. Even though it had been practiced by ancient Chinese and Egyptians, Americans considered embalming unnecessary and extravagant.

But then the Civil War inflicted mass casualties – at least 620,000 soldiers died, often on battlefields far from home. To bring those bodies home, Meyer said, they had to be embalmed.

In fact, she noted, as soldiers boarded trains to head off to war, intrepid salesmen tried to sell them prepaid embalming and transportation services in the event of death.

“If the soldier bought into that, they would be given a little card that said that they had paid for their own embalming and transportation back home should they die in battle,” Meyer said. Those sales pitches were “not good for morale, as you might imagine, and the U.S. military shut that down pretty quickly.”

During the mourning period, survivors often wore pendants or other jewelry containing hair from the deceased, Meyer said. These items of jewelry were made in advance – not from hair pulled from the corpse.

For example, women would collect strands of hair from their hairbrushes and weave them into intricate patterns.

“These ‘hairlooms,’ if you will, were passed down from generation to generation. People would add to them. They might contain your grandma's hair and your mom's hair and your daughter's hair and your husband's hair,” Meyer said.

Men indicated they were in mourning by wearing a black armband or ribbon or a black pin from a fraternal organization. “You would have a special one made that was all black to represent that you had lost someone close to you,” Meyer said.

Old City Cemetery features ornate ironwork and stonework. Grave markers often display religious symbols – usually a cross but also doves, scrolls or a finger pointing toward heaven.

Meyer also has researched the mourning rites of Black residents from centuries ago. When they were enslaved and brought to the Americas, they brought along certain African customs – such as draping mirrors in black after someone dies.

“They believed that if you saw yourself in the mirror while there was a deceased body in your home, that you could be the next to join them,” Meyer said.

Another African American custom was to hang bottles on the branches of a tree near the deceased’s grave or home – creating a “bottle tree.”

“The intention was that evil spirits or things that you did not want in your home would be attracted to those brightly colored bottles, and they would get trapped inside,” Meyer said. “This was a way of protecting your home or your graveyard where your loved ones were buried from things that were evil or malicious or had bad intent.”

One of the saddest stories about people buried in Old City Cemetery involves an African man named Ota Benga. A native of the Congo in central Africa, he was brought to the United States and exhibited as an exotic “pygmy” at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair.

Benga longed to return to Africa, but his hopes “were stymied by World War I,” according to an online biography. “He grew increasingly despondent and eventually took his own life with a gun on March 20, 1916.”

Records showed that Benga was buried in a rosewood casket in Old City Cemetery; however, the grave’s location and any marker have been lost to time.

Free walking tour of Old City Cemetery

Ashleigh Meyer, the cemetery’s director of historical research, will offer a guided tour of the grounds and buildings from 10 a.m. to noon on Thursday, Aug. 10.

The tour will include viewing and instruction regarding the cemetery ironwork, plants, family plots, beekeeping operations, the Caretakers’ Museum and Pest House Medical Museum.

Some motorized assistance (golf carts) will be available for those with limited walking ability.

The event, hosted by AARP Virginia, is free; however, registration is required.