AARP Hearing Center

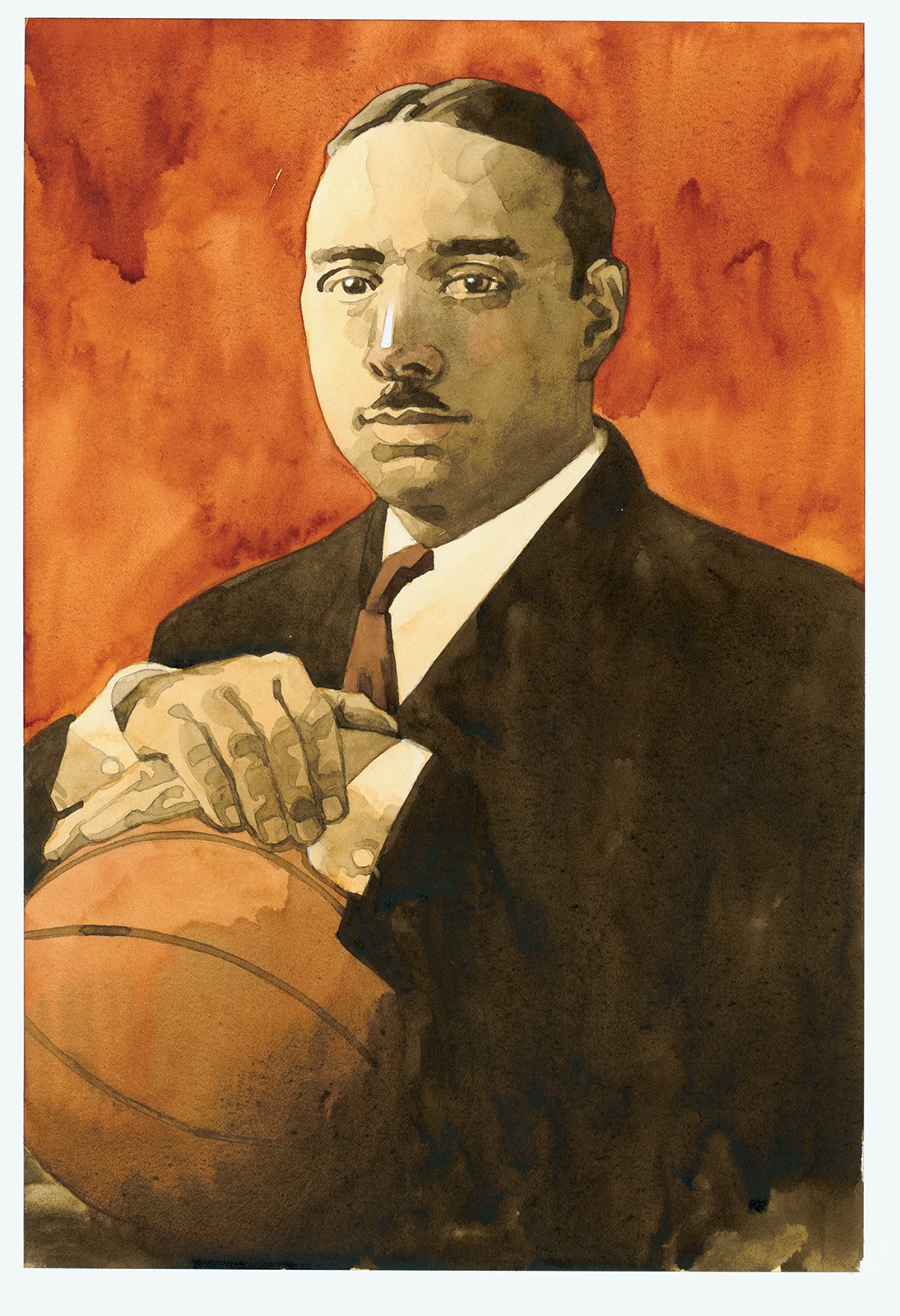

Basketball is a global phenomenon that attracts millions of fans, but few may know the pioneering role that a young African American physical education teacher, Edwin B. Henderson, played in the early days of the sport.

Henderson, who grew up in Washington, D.C., and lived many years in Falls Church, Virginia, was dubbed “the grandfather of Black basketball” for bringing the sport to African American men who were shut out of organized activities during the Jim Crow era of the early 1900s.

Later in his long career, Henderson founded a branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People in Northern Virginia and withstood threats and harassment while fighting to desegregate the state’s schools.

His story was told by his grandson, Edwin B. Henderson II, a retired educator and local historian, in a recent presentation of the AARP Tuesday Explorers series. The program can be viewed on the AARP Virginia YouTube channel.

Henderson, who was born in 1883, learned about basketball from its founder, James Naismith, while becoming certified as the first Black physical education teacher in the country at Harvard University. The game was a good sport for low-income kids, but it required organization, indoor facilities and teachers at a time when Black schools were neglected.

Henderson established teams in the nation’s capital a little less than two decades after the game was created. He organized leagues up and down the East Coast, trained referees and officials and wrote manuals.

He also served as director of the Department of Physical Education for the District of Columbia’s Black public schools. He wrote numerous pieces for periodicals including Crisis, The Messenger, and the Negro History Bulletin. In 1939, Henderson authored The Negro in Sports, the first major study of Black athletes and athletics.

“He was the first to introduce the game of basketball to African Americans on a wide-scale, organized basis in the nation during the era of abject Jim Crow segregation,” said his grandson.

For years, Henderson II and his wife Nikki proudly advanced E. B. Henderson’s legacy as a trailblazer. In 2013, their efforts earned the posthumous induction of E.B. Henderson into the Naismith Memorial Basketball of Hall of Fame in Springfield, Mass.

E. B. Henderson and his wife Mary Ellen also worked tirelessly as civic activists for racial justice. He organized the Fairfax County chapter of the NAACP, and fought Virginia’s efforts, known as Massive Resistance, to block desegregation of public schools.

Those efforts brought him hate mail, threats against his family and a cross burning on his property. His grandson, during the presentation, showed a vicious letter sent to Henderson by the Ku Klux Klan.

Through it all, Henderson never wavered from insisting that Black Americans deserved equal opportunity, from the basketball court to the classroom.

“Once the Negro is afforded access to equal facilities and training, whites will find the Negro equal or superior in every athletic endeavor,” he wrote in the early 1900s.

“That was a bold statement,” his grandson said.

Henderson lived to see schools integrated in Virginia, including Fairfax County in 1965. Black student athletes excelled in sports.

He died in 1977 at the age of 93 in Tuskegee, Ala., where he and Mary Ellen had retired. She died one year before him.

Henderson’s life of distinction is well documented. Last year, a state historical marker was placed in his honor at the sight of E.B. Henderson’s home in Falls Church.