AARP Hearing Center

At the start of World War II, German U-boats were inflicting heavy losses on Allied ships. The Nazis coordinated their attacks by sending coded messages using an encryption system that “seemed to be unbreakable,” said Dan Sherman, an AARP Community Ambassador and expert on the subject.

“The British desperately wanted to break these codes, particularly the naval codes, because U-boats were out there in the North Atlantic” blowing up supply ships, Sherman said.

So the British government recruited teams of scientists to try to decipher the Germans’ Enigma code. Ultimately, a mathematician named Alan Turing came up with a strategy to crack the code and disrupt the Nazis’ war plans, said Sherman, a retired economist and popular instructor for the Lifelong Learning Institute of Virginia Tech.

He said historians estimate that Turing’s work, which remained secret for decades, “shortened the war by two years,” saving millions of lives. “The man was absolutely brilliant.”

Sherman, who holds a Ph.D. in economics from Cornell University and recently retired from the American Institutes for Research, discussed Turing’s role during a Nov. 7 webinar held by AARP Virginia in collaboration with the Lifelong Learning Institute.

How the Enigma system worked

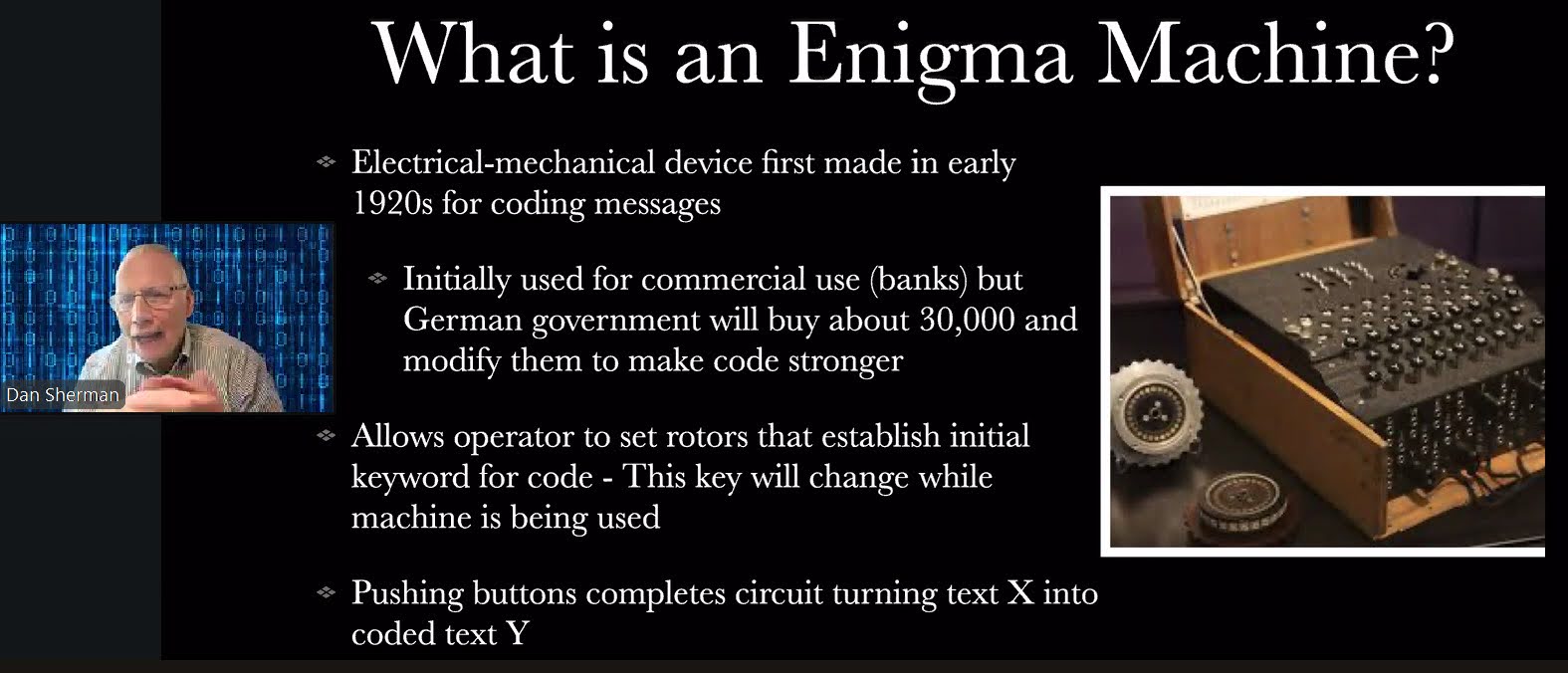

During World War II, all branches of Germany’s military used a device called an Enigma machine to code and decode messages, Sherman said. Like a decoder ring with multiple rotors, the machine scrambled the letters of the alphabet – so that an A, for example, might actually stand for an M or a T.

The Enigma machine didn’t simply shift each letter by a predictable number (such as A becoming B, B becoming C, and so on). Instead, it re-assigned letters almost randomly. “Rather than shifting it one, you shift it a different amount each time,” Sherman said.

“Essentially, every letter had its own shifting, and it just seemed to be random.”

Moreover, the Nazis’ machine had an ingenious way of handling double letters. If it were coding the word “hello,” for example, the system would assign the first L one letter and the second L a different letter.

“There's no pattern to this; there's no way to know what it's going to be next,” Sherman said. “So you can see why the Germans thought they had an unbreakable code.”

The key to deciphering the code would be a phrase in the weather report that the Nazis would broadcast by radio at 6 o’clock each morning. The key phrase, and thus the entire code, changed every day.

The English “could hear what the Nazis were sending over through the airwaves. They just couldn't understand it,” Sherman said.

Turing exploits a flaw in Nazis’ coding

Sherman said the Allies got their hands on an Enigma machine. “That wasn't the difficult part.”

The trick was quickly determining how the machine had scrambled the letters in each day’s message.

In 1939, the British government established a top-secret center for code breaking at an estate called Bletchley Park, about 50 miles north of London. At its peak, the operation employed about 10,000 people, “all sworn to secrecy,” Sherman said. “The center of the drama: Alan Turing.”

Turing had been born in 1912 – an “awkward child” who liked math and science, Sherman said. Turing attended Cambridge University and then earned a doctorate degree from Princeton.

Turing seized on a flaw in the Enigma machine: “the fact that you couldn’t code a letter to itself,” Sherman said. In other words, an A could correspond to any other letter except A.

Sherman said that realization gave Turing “a way of accessing – breaking down – the Enigma code.” He programmed a machine, called the Bombe, to unscramble the Nazis’ message each day in less than half an hour.

“Turing's logic and some machinery and some really clever ideas got it down to about

20 minutes,” Sherman said.

But the British had to make tough decisions after Turing discovered how to crack the Enigma code. “You don't want the bad guys to know you can read the code,” Sherman said. “The moment they discover you can read their code, they're going to change it.”

Turing created a statistical model to select which intelligence to act on so the Allies could maximize their efforts to thwart the Nazis while raising a minimum of suspicion.

As a result, the British didn’t act on every decoded message. Sometimes, they repositioned Allied ships or troops, for example, to avoid an attack by the Nazis. But other times, they let such an attack proceed – even if it means lives were lost.

Turing’s life, death and legacy

While he was at Bletchley Park, Turing’s personal life became an issue.

“In the Cold War period after the war, being gay could be a problem,” Sherman said. Homosexuality was a crime in Great Britain, the United States and many other countries. “You could set yourself up for potential blackmail and such, so the authorities didn't take well to it.”

In 1952, Turing was charged with gross indecency and convicted. To avoid prison so he could continue his work, “he underwent what is called chemical castration – he just took large doses of female sex hormones that were supposed to reduce his libido,” Sherman said.

On June 7, 1954, after a year of government-mandated hormonal therapy, Turing died of cyanide poisoning. An inquest ruled the death a suicide, “but there's some suspicious things here,” Sherman said. “People debate, you know: Did he kill himself? Was he killed?”

What isn’t open to debate, he said, is Turing’s “absolute importance” to helping the Allies defeat the Nazis.

In 2013, Queen Elizabeth II granted him a posthumous pardon. And in 2017, the British Parliament passed the “Alan Turing law” giving amnesty to men who had been charged in the past with crimes related to homosexual conduct.

Turing, whose face is on British currency (the £50 banknote since 2021), is “still very much with us,” Sherman said. His work laid the foundation for the development of computers and the digital age.

Turing is “considered one of the greatest mathematicians and contributors to computer science of all time, even though he died at age 42,” Sherman said.

He said that “because of the secrecy around the Enigma Machine and breaking it,” people didn’t know about Turing’s contributions until the 1980s.

In 2014, Turing was the subject of “The Imitation Game,” an award-winning film starring Benedict Cumberbatch. The title of the movie refers to a game Turing proposed for answering the question “Can machines think?” in a paper in 1950.

More about the Enigma Machine, coding and Alan Turing

Dan Sherman compiled a list of resources for learning more about these topics. He recommended:

- A video showing how the Enigma Machine works

- A video about the flaw in the machine that made the code easier to read:

- A detailed discussion of the Enigma Machine and code-breaking methods

- A free, hourlong documentary on Alan Turing

Sherman also suggested books such as:

- The Code Book: The Evolution of Secrecy from Mary, Queen of Scots to Quantum Cryptography

- The Codebreakers of Bletchley Park: The Secret Intelligence Station that Helped Defeat the Nazis

- The Essential Turing: The ideas that gave birth to the computer age