AARP Hearing Center

Before you read this, take a second and think of the very first time you can remember playing outside with friends. What were you doing? Were you with children of the same gender and age? Were you in the presence of an adult? Were you wearing a uniform of any kind?

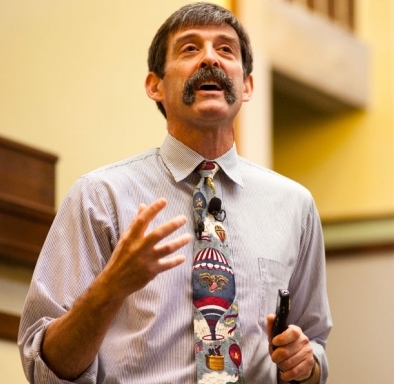

If you answered “no” to these questions, you were a “free-range kid” according to Mark Fenton. Fenton claims that children don’t play outside like they used to, he explained the built environment and social barriers to free-range play to a group of community members gathered at a Healthy Polk 2020 meeting Saturday morning.

I think of my own childhood, and remember playing a scavenger hunt game my neighborhood friends had invented before houses on our block installed fences, and curfew was still based on the sun. My family moved to this neighborhood when I was seven, to a home located on the edge of Marion, Iowa. Cornfields surrounded our house for those first few years, I used to explore them and pretend to get lost.

I played with various ages of boys and girls, we had no direct adult supervision, and were certainly not part of an organized game that required uniforms. I was a free-range kid, perhaps the last generation, but I agree with Fenton.

So what now? The timing of Fenton’s visit to Des Moines was critical. His presentation coincided with the open public comment of the Des Moines Area Metropolitan Planning Organization’s long-range plan, as well as a growing public dialogue of walkability and bikeablity. We’ve known we need to make changes, but Fenton provoked a real sense of urgency.

Fenton says we’re experiencing a “twin epidemic” of physical inactivity and poor nutrition. People commute by foot and bike less, and drive more. One in five of American adults meet the recommended 30 minutes of daily physical activity, and 365,000 annual deaths can be linked to sedentary lifestyles and nutrition, which is second only to tobacco-related deaths. The good news? People are starting to realize the system isn’t sustainable. Walkable residences have higher home value, and big box stores and large malls on the outskirts of town are becoming less desirable.

Fenton aimed to help community conversations get started. He demonstrated how easy it is to fight for livability principles in practice by acting out a scenario in which he received pushback from a city official in passing an elevated bike lane. “I don’t care if you won’t use it or not!” he exclaimed. He continues by defending a bike commuter, “His is one less car on the road, he has a smaller carbon footprint, and you will still benefit when your healthcare costs will decline when he doesn’t die of a heart attack.”

Fenton’s argument is hard to deny, and his data certainly demonstrates a clear picture. We already know the systems change necessary to create more livable environments; it’s the way we stand up for these policies and practices that can make a real difference. So, what can you do?

Do you think kids growing up now are free-range? Learn more about this idea from Mark Fenton’s presentation. What if Polk County residents have a chance to change that with a long-range community plan that benefits people of all ages? Read the long-range goals for Greater Des Moines in Mobilizing Tomorrow and give your opinion while you have the chance to make a difference. Comments will be taken until 4:00 pm on Wednesday, November 19, 2014, and can be emailed to nfo@dmampo.org.