AARP Hearing Center

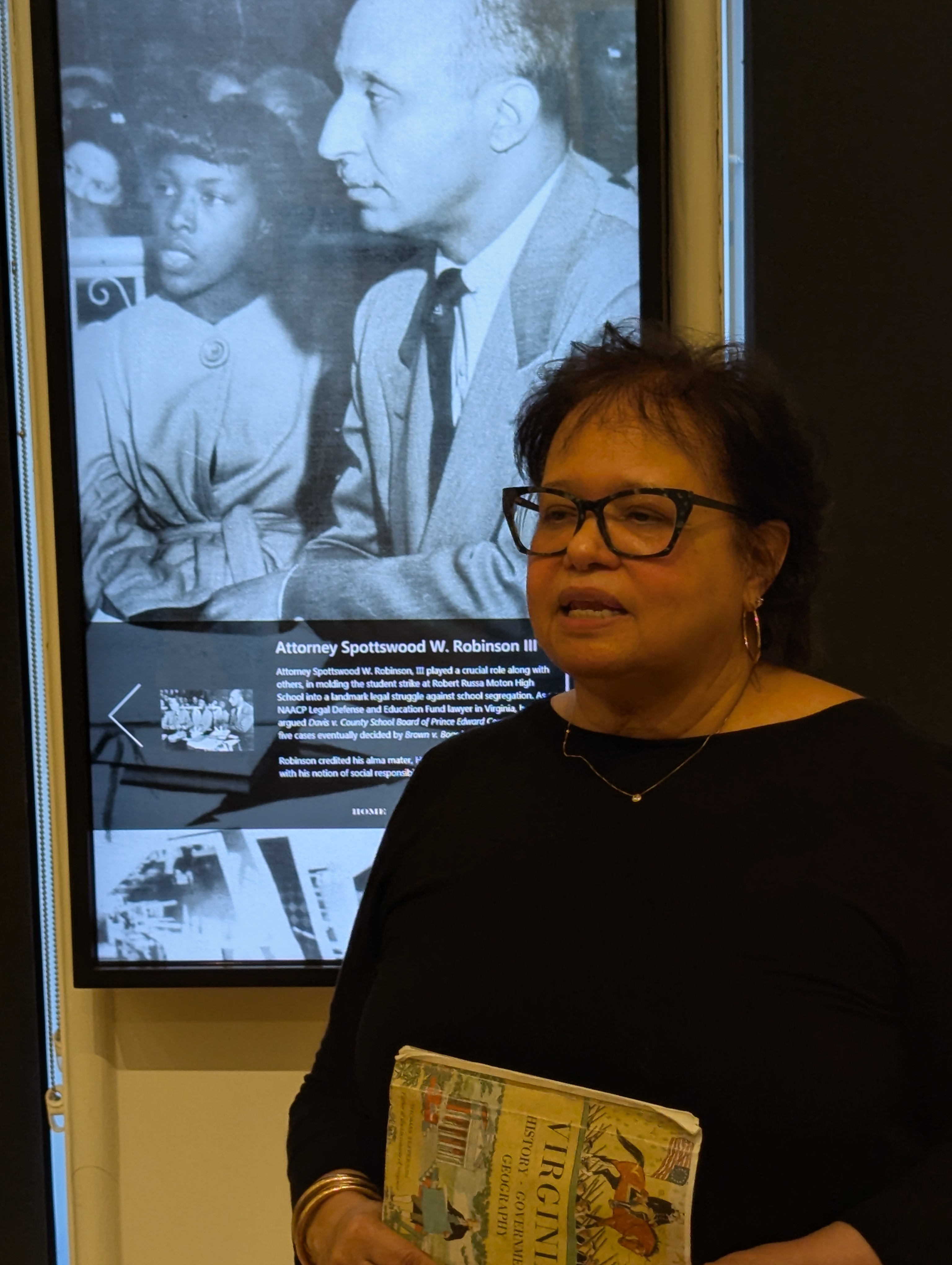

Faithe Norrell clutched a book titled “Virginia: History, Government, Geography” as she led a tour recently of the Black History Museum and Cultural Center of Virginia. The tour began at an interactive timeline noting that, in 1619, a slave ship brought about two dozen Africans to Point Comfort in the newly established Colony of Virginia and traded them for supplies.

They were the first of more than 12 million people who were kidnapped in Africa, held in chains in the hulls of ships, taken to the Americas and sold as slaves. Millions more died during the journey. The trans-Atlantic slave trade, which continued until the late 19th century, was one of the most violent and horrific eras of world history.

But you wouldn’t know that from the textbook in Norrell’s hands. It showed a dapper Black man arriving at a port with a suitcase and his smartly dressed family and being welcomed with a handshake by a white man. Virginians treated slaves kindly, the book claimed. “They knew the best way to control their slaves was to win their confidence and affection.”

Until the 1970s, generations of Virginians were indoctrinated with such fictitious propaganda, which portrayed slavery as benign, the American Civil War as a noble effort to defend the Southern way of life, and Confederate soldiers as heroic and saintly.

“This is the ‘Lost Cause’ false narrative,” said Norrell, a retired teacher whose grandparents were born enslaved in Virginia. She called the textbook “a pack of lies.”

The “Lost Cause” myth “perpetuated a dishonest depiction of the slavery system,” Norrell said. She said it was promulgated by groups such as the United Daughters of the Confederacy and “often still exists.”

The Black History Museum and Cultural Center of Virginia, or BHMVA, exists to set the record straight. Its mission is to share, interpret, preserve, exhibit and commemorate the rich history and culture of African Americans in Virginia and beyond.

The museum, at 122 W. Leigh St. in Richmond, is open Wednesday through Saturday. To mark Black History Month, AARP Virginia is offering group tours of the BHMVA every Friday during February.

Painful horrors and inspiring successes

The museum’s exhibits underscore the brutality and indignities inflicted upon African Americans as well as the contributions and achievements that Black Virginians have made despite racism and segregation.

Past a 35-foot touch screen offering a historical timeline, the first-floor galleries focus on the Emancipation, Reconstruction, Jim Crow, Desegregation, Massive Resistance and Civil Rights eras. Exhibits highlight such Virginians as:

- Powhatan Beaty, who won the Congressional Medal of Honor as a commander in the 5th U.S. Colored Infantry during the Civil War.

- Elizabeth Keckley, who bought her freedom from slavery, established a dressmaking business in Washington, D.C., and became a seamstress and confidant to first lady Mary Todd Lincoln.

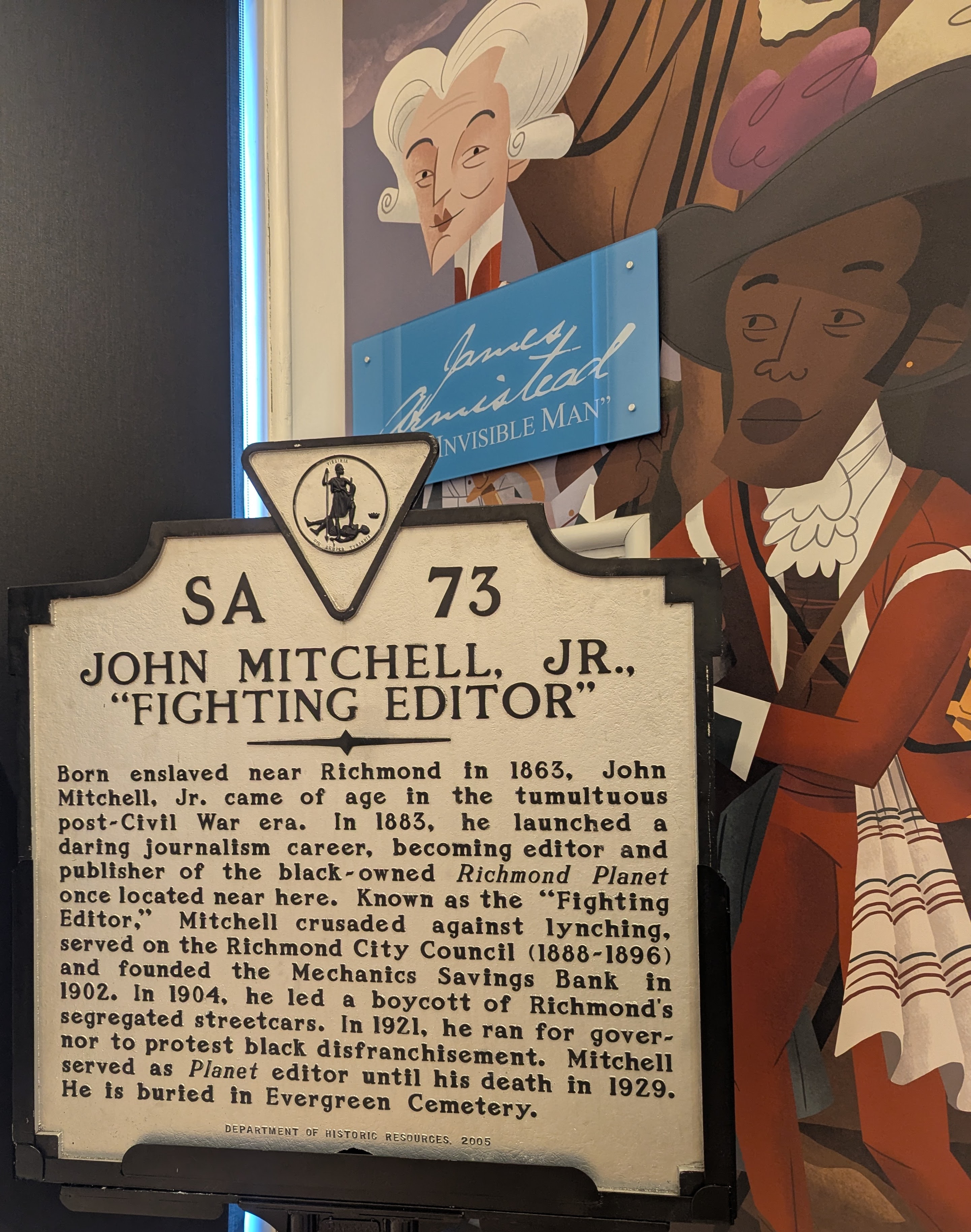

- John Mitchell Jr., who edited the Richmond Planet newspaper, campaigned against lynchings and other injustices, and pushed for political power and economic development in the Black community.

- Maggie Walker, the first Black woman to serve as a bank president in the United States and an advocate for racial equality, women’s rights, education and entrepreneurship.

The BHMVA has a 13-foot plaster cast of the tennis star and humanitarian Arthur Ashe, a Richmond native. The model was used to create the statue on Monument Avenue. The museum also includes a tribute to the Emancipation Oak, a tree on the Hampton University campus where, in 1863, the Emancipation Proclamation was read for the first time in the South.

The museum’s second level showcases nationally traveling exhibits as well as works by local artists and community organizations.

The upper galleries currently feature “A Prescription for Change: Black Voices Shaping Healthcare in Virginia,” which provides an overview of African American achievements in medicine, dentistry, pharmacy, nursing and other health professions.

The exhibit spotlights contemporary as well as historical figures. They include Peter Hawkins, Richmond’s “designated tooth-drawer” in the 1700s; Dr. Alexander Augusta, a surgeon with the Union Army during the Civil War; Dr. Richard Tancil Sr., who helped create the Richmond Hospital Association in the 1800s; Dr. Zenobia Gilpin, president of the Richmond Medical Society and a founder of the Virginia State Conference of the NAACP; Dr. William Ferguson Reid Sr., who in 1967 became the first Black person elected to the Virginia General Assembly in the 20th century; and Basmah Karriem, a “grand doula,” childbirth educator and founder of Mother of Civilization Birth Services in Richmond.

Also on the second floor is an exhibit titled “We Are the Builders: Honoring the Contributions of Black Labor in Virginia.” It showcases tools that Black people have used “in sustaining the economy of the Commonwealth of Virginia and the nation.”

“African Americans have influenced progress and been a vital force in the workplace, despite discrimination, poor working conditions and unequal compensation,” the exhibit notes.

Guides provide context and perspective

Tours are led by experts like Faithe Norrell, who was a teacher and librarian with the Richmond Public Schools for 42 years before retiring in 2017. She has been with the BHMVA for five years, currently as a cultural heritage specialist.

Norrell knows the history because she and her family have lived it. Her grandfather, Albert V. Norrell, was born enslaved in 1857. After the Civil War, he graduated from the Richmond Colored Normal School, a high school and teacher training program established during Reconstruction, and then taught in the Richmond school system for 66 years.

“He also established a tradition in our family,” Norrell said. More than 30 members of the family have taught in the Richmond Public Schools, she said.

During the tour, Norrell described the appalling racism that African Americans faced in Virginia. “We weren’t thought of as people; we were thought of as property.”

Norrell said slave owners raped female slaves and created breeding operations to increase – and then sell – the number of people they held in bondage.

A stone’s throw from the Virginia Governor's Mansion was a slave market from which “over 300,000 Blacks were sold to the down-river slave trade to work in the very lucrative rice, sugar, and cotton plantations in the South,” Norrell said.

Although slavery officially ended after the Civil War (except as punishment for a crime), racism didn’t. Virginia passed Jim Crow laws to disenfranchise African Americans, arrest them on trumped-up charges, impose racial segregation and bar Black citizens from educational and economic opportunities.

In 1924, for example, the Virginia General Assembly passed the Racial Integrity Act, which established strict racial categories (anyone with at least “one drop” of African American blood was considered Black), banned interracial marriage and led to the forced sterilization of thousands of people.

Norrell noted that Adolf Hitler admired the Virginia law: It was the model for the Nazis’ plan to create a master race.

Teenager led fight against segregation

School segregation in Virginia also resonated outside the commonwealth, exhibits at the BHMVA explain.

In 1951, students at a Black high school in Prince Edward County walked out to protest the separate and unequal conditions to which they were subjected. Norrell noted that the strike was led by 16-year-old Barbara Johns in what many historians consider the start of America’s desegregation movement.

As a result, Virginia lawyers Oliver Hill and Spottswood Robinson sued on behalf of the students. The case was combined with four others from across the United States. In 1954, in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, the U.S. Supreme Court declared racial segregation in public schools unconstitutional. The court ordered states to comply with “all deliberate speed.”

Virginia responded with a policy of “Massive Resistance” – closing public schools rather than integrate them. Prince Edward County’s public schools did not reopen until 1964.

“These children lost the opportunity of an education,” Norrell said. “If you take away your education, you take away your trajectory in life.”

Jackson Ward, once called ‘Black Wall Street’

While Blacks faced hardships in many parts of Virginia, Norrell said, they enjoyed success in some neighborhoods.

“If you lived in a city like Richmond, you didn’t feel the sting of segregation” as much, she said. That was especially true in Richmond’s Jackson Ward, where the city’s most prominent Black citizens lived and where the BHMVA is located.

During the first half of the 20th century, Jackson Ward developed a Black middle class, a vibrant business community and a reputation as “Black Wall Street” and the “Harlem of the South.” The neighborhood was insular and self-sustaining, Norrell said.

“We had excellent schools,” she said. “We had all the amenities,” with music teachers offering private lessons in the evenings and a dance teacher coming from Washington each week to teach children ballet.

Jackson Ward’s success was cut short in the 1950s when city and state officials put a highway through the heart of the neighborhood, razing about 1,000 homes and businesses and displacing an estimated 7,000 Black residents.

The Black History Museum, which opened to the public at a different location in 1991, is in a building that dates to Jackson Ward’s heyday.

It was constructed in 1895 as the Leigh Street Armory, a training center for a Black battalion in the equivalent of that era’s National Guard. Four years later, Virginia’s governor disbanded all African American militia units. The building later served as a school and, during World War II, as a social and recreational center for Black servicemen.

In the early 1980s, fire almost destroyed the building and it fell into disrepair; however, federal grants helped restore the structure. In 2016, after years of planning and fundraising, the BHMVA moved to the Leigh Street Armory.

Last year, the museum was recognized by the UNESCO (the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) and the National Park Service for its efforts to educate the public.

Planning your visit:

The Black History Museum and Cultural Center, 122 W. Leigh St. in Richmond, is open from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Wednesday through Saturday. Tickets cost $10 for adults ($8 for seniors). More information is available by visiting blackhistorymuseum.org or calling 804-780-9093.