AARP Hearing Center

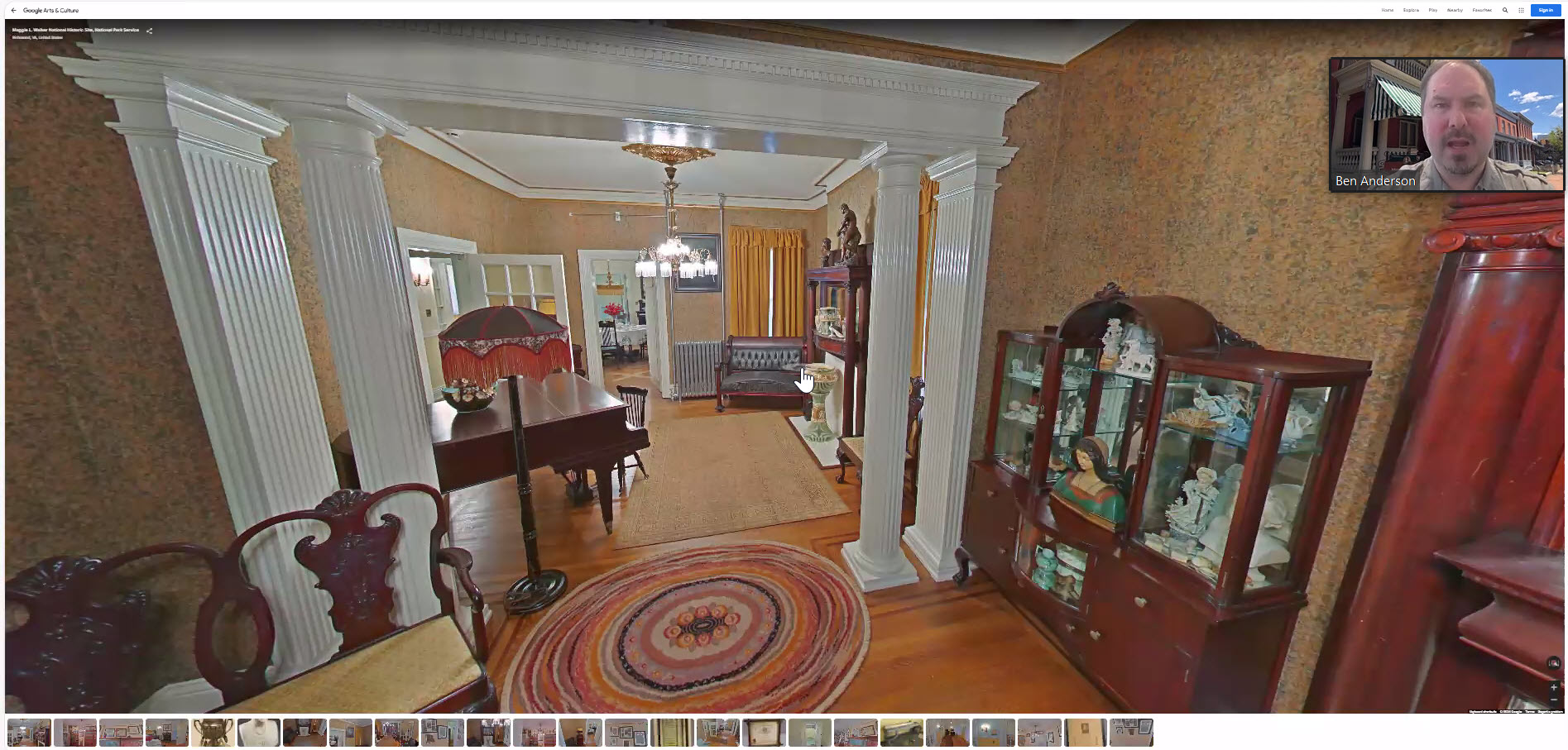

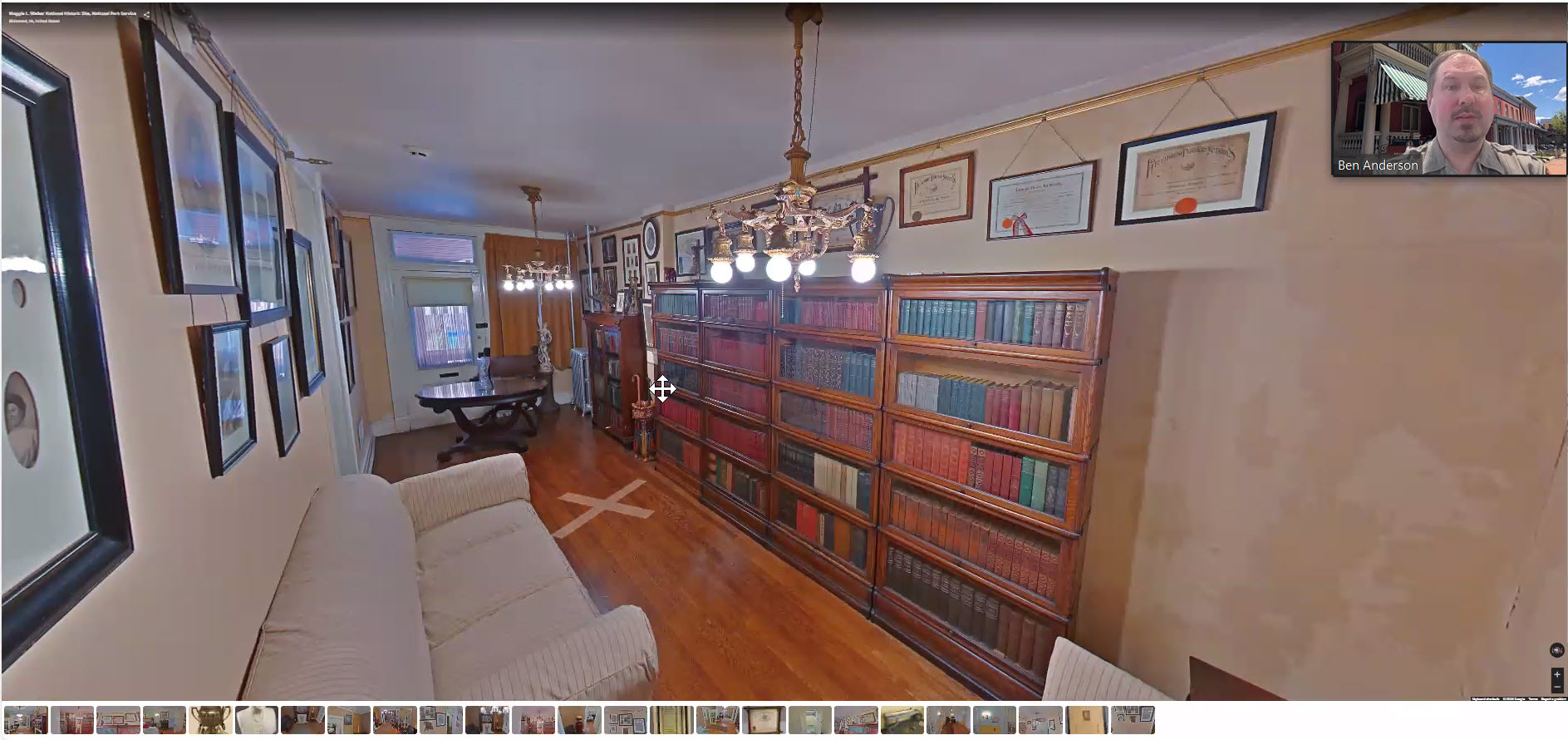

An ornate parlor with a baby grand piano. A library with hundreds of books and framed diplomas. All part of a 28-room “urban mansion” that housed four generations of her family.

That describes the Maggie L. Walker National Historic Site – the home in Richmond, Virginia, where Walker, a trail-blazing African American businesswoman and civil rights leader, lived from 1905 until her death in 1934.

“When I walk through the halls of this house, honestly, I feel like the family’s still there – they've just stepped out of the room for a moment,” said Mark Wilcox, a ranger with the National Park Service, which provides free tours of the home in Richmond’s Jackson Ward neighborhood.

By visiting the home, Wilcox said, “you can learn so much” and draw inspiration from Walker’s life story. In the face of virulent racism and sexism, she chartered a bank in 1903, becoming the first Black woman in the United States to serve as a bank president.

Throughout her life, Walker advocated for racial equality and women’s rights; championed entrepreneurship and education, especially for African Americans and for women and girls; and worked with numerous service and philanthropic organizations.

On Feb. 1, AARP Virginia kicked off Black History Month by organizing an online presentation about Walker and a virtual tour of her home – a two-story Victorian Gothic brick row house built in 1883.

The house, which Walker’s descendants deeded to the National Park Service in 1978, has been “preserved as a tribute to her enduring legacy of vision, courage, and determination.” Besides documenting Walker’s life, the home also reflects the vibrancy of the African American community in Richmond during the days of racial segregation and oppression of the early 20th century.

Racist stereotypes at the time portrayed Black people living in poverty and squalor. But Jackson Ward – where nearly everyone was African American – had a self-sustaining economy known as “Black Wall Street,” bustling with restaurants, theaters and other businesses.

The daughter of a once-enslaved woman, Walker was born in 1864. After graduating from Richmond Colored Normal School in 1883, she taught for three years at a public middle school. In 1886, she married a brick contractor, Armstead Walker Jr.

Under school policy at the time, as a married woman, Walker had to resign her teaching position. So she started working for a fraternal group called the Independent Order of St. Luke, turning it from a near-bankrupt burial society into an organization with more than 100,000 members across 26 states and an engine for economic empowerment for the Black community.

Under the organization’s banner, Walker established a newspaper and a department store as well as St. Luke Penny Savings Bank. (It later merged with another institution to become Consolidated Bank and Trust, now part of Peoples Bank.)

In 1904, Maggie Walker bought the house, which then had only five rooms, for $4,800, Wilcox said. Interestingly, he said, Armstead Walker’s name was not on the deed – a reflection, perhaps, of Maggie Walker’s independence at a time when women weren’t even allowed to vote.

Over the years, the house was renovated and expanded to include 28 rooms. At one point, about a dozen people lived in the home, including Maggie Walker’s mother and Maggie and Armstead Walker’s children and grandchildren, said National Park Service ranger Ben Anderson.

In her home, Maggie Walker fostered “a large, close-knit family environment,” Anderson said. He noted “how dedicated she remained to her family even in the context of a very busy and demanding professional career.”

At their house, Anderson said, the Walkers hosted a procession of the era’s most prominent African American luminaries, including Booker T. Washington, the influential educator and orator; W.E.B. DuBois, a founding member of the NAACP and editor of its magazine, The Crisis; Mary McLeod Bethune, an educator, businesswoman and social activist who advised Presidents Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Harry Truman; and Langston Hughes, a poet, playwright and novelist who shaped the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s.

Anderson provided a room-by-room description of the Maggie Walker House during the virtual tour, which drew online users from New York, Texas, California and other states.

Maggie and Armstead Walker had sons named Melvin and Russell and adopted a daughter, Polly. The children – and later the grandchildren – took piano and violin lessons in the parlor, Anderson said.

He also described the home’s library, which features the original bookcases containing about 600 books – testimony to Maggie Walker’s emphasis on the value of education.

During her life, Walker faced challenges beyond patriarchal prejudice and Jim Crow laws that dictated where Blacks could live, prevented them from voting, often relegated them to low-paying jobs and forced them to sit in the back of buses or streetcars.

She also faced personal tragedies: When Walker was 11, her father died under suspicious circumstances, sending the family into poverty. In 1893, Maggie and Armstead Walker had a son who died seven months later. In 1915, their son Russell accidentally shot and killed Armstead Walker after mistaking him for a burglar. Russell Walker then sank into depression and died at age 32.

Moreover, Maggie Walker suffered from diabetes. In her 60s, because of diabetic paralysis, she needed a wheelchair – and had one customized with a detachable writing desk. Visitors to the Maggie Walker House can see a reproduction of her “rolling chair,” as well as the hand-operated, rope-and-pulley elevator that she used to travel between the first and second floors.

On Dec. 15,1934, Walker died at home of diabetic gangrene. She was 70 years old.

Besides the designation of her home as a National Historic Site, she has been honored in other ways. For example, the Maggie L. Walker Memorial Plaza in Jackson Ward features a 10-foot bronze statue surrounded by 10 benches noting her achievements. The Virginia Women’s Monument at the State Capitol also includes a statue of Walker.

After her death, Jackson Ward – once known as the “Harlem of the South” – continued to bear the brunt of redlining and other racist practices. Under the guise of urban renewal, for instance, authorities bulldozed about 3,000 homes in Walker’s neighborhood to make way for public housing projects and a freeway

In recent years, Jackson Ward has been making a comeback as young professionals move there to be close to downtown. Restaurants and other businesses have sprouted in the neighborhood, real estate values have risen, and officials are considering ways to reconnect the sections of Jackson Ward that had been split by the construction of Interstate 95.

But the beneficiaries of such revitalization look different from the people living in Jackson Ward during Maggie Walker’s time. Because of gentrification, the neighborhood’s population is now “roughly 70% white,” Wilcox explained during the virtual tour.

It’s impossible to know what Maggie Walker would make of such changes. But she likely would urge people to continue to fight for fair treatment and equal rights.

“The greatest power on earth for the righting of wrongs is the power of agitation,” Walker wrote in the St. Luke Herald, the newspaper she founded, in 1914. “When the spirit and power of agitation die among a people, they are doomed beyond all hope of resuscitation and redemption.”