AARP Hearing Center

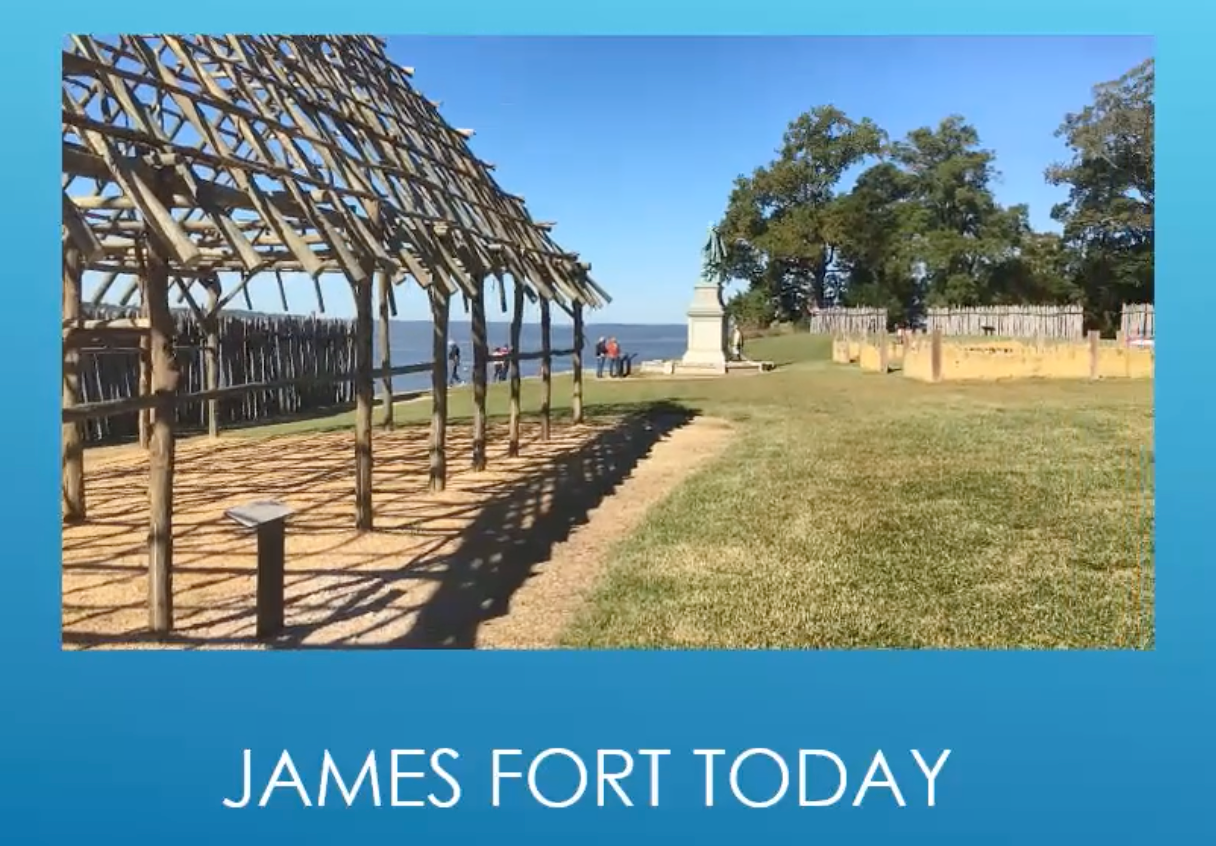

Today, most of us think about Jamestown as the first successful English colony in America, and the fort where its first residents struggled to survive. However, this is just a part of the Jamestown story. This webinar, the third in AARP’s Virginia Treasures Series, examines the events starting in 1619 that brought the first documented Africans to Virginia and marked the beginning of slavery in English North America.

This webinar was presented on April 21, 2021, and introduced by Dorothy Ware, AARP Virginia Volunteer. The program was presented by Mark Summers, director of Public and Youth Programs at Historic Jamestown, and the public historian for the Jamestown Rediscovery Project. Over 200 AARP members and guests from around the country attended this virtual historic program.

Summers argues that in order to understand early Jamestown, you need to know that Jamestown was founded by England as a business by wealthy businessmen. This is key to understanding how slavery can happen when technically it is not legal. The businessmen formed the Virginia Company, and petitioned King James for a Charter to establish a colony in Virginia. They promised the King about 20 per cent of the profits. The colony was established in 1607 but was a failure during its first five years from 1607 t0 1612. During this time many of the colonists died of disease, starvation and incompetent leadership.

The fortune of Jamestown improved when John Rolfe introduced Spanish-seed tobacco into Virginia in 1611. Tobacco became an important cash crop and was making Virginia planters wealthy by 1619. Additionally, John Rolfe married Pocahontas, the daughter of the local Native American leader Powhatan which brought peace for the Jamestown settlement for a few years. In 1619, Jamestown created the first General Assembly as its governing institution.

In late August of 1619, the course of American history changed. A Man of War ship, the White Lion, from the Netherlands arrived off the coast of Hampton, Virginia bringing about 20 Africans who were purchased by Jamestown businessmen. A second ship, called the Treasurer, also brought a small number of Africans in 1619. Summers researched these transactions over a period of four years and concluded the ships were English and not Dutch, and were likely pirate vessels. Summers believes the origin of the ships was concealed from the English government to protect the colony’s business interests and not arouse suspicion over the first purchase of slaves in the colony. This was the beginning of two and a half centuries of slavery in North America.

Summers also researched the origin of the trans-Atlantic slave trade in Africa and concluded that the first Africans in Virginia came from the Ndongo Kingdom in what is modern Angola today. He traces the first shipment of African Angola slaves to the Spanish slave ship San Juan Bautista, which was overtaken by the White Lion, in a pirate action off the coast of Mexico. After arriving in Jamestown, they were placed in servitude in local homes and plantations.

Both slavery and indentured servitude grew quickly in Virginia to meet the demands of the plantation economy. The legal system, to support slavery developed slowly, and Summers has found no local laws passed before 1662 to support slavery. He relates that, in England, the common law was that no one could legally be a slave. However, in the Virginia colony, the governor and Governor’s Council established a “law of custom” that supported the needs of the colony. In 1662, Virginia planters introduced the first slave law to define slave status and prevent African freedom. Between 1680 and 1705, further laws were passed to segregate and separate white and black Virginians. Summers states that these measures allowed race-based slavery, with legal protection, to become the law. In 1691, marriage between white and black people became illegal in Virginia, and this remained the law until 1967.

Summers explains that the race separation in Virginia and the south was social rather than physical. For people who broke this culture, the result of violence was all too real. As a traveling school teacher, Summers relates how he saw that race separation has continued to this day. He offers that the solution is to have a dialogue where we all come to understand one another. And knowing where we came from, is the first step to getting better. He concludes that we can never solve race problems if we don’t know how they happened.