AARP Hearing Center

By Hilary Appelman

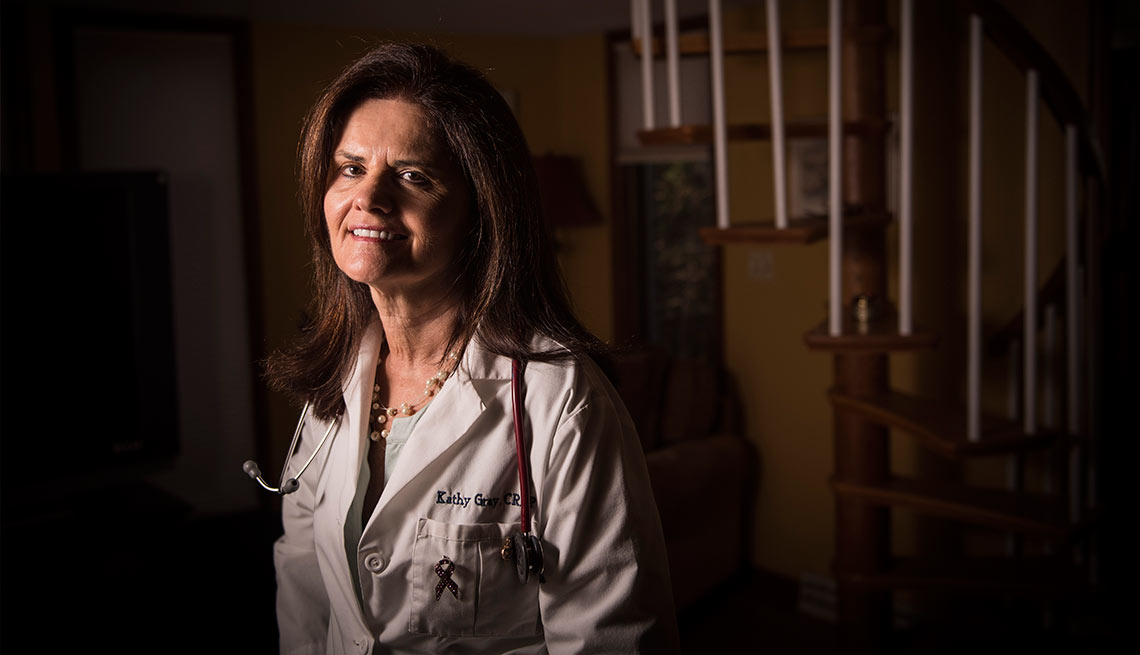

On any given day, Kathy Gray might give a newborn a well-baby exam, diagnose a child with flu, prescribe medication for an underactive thyroid, order a colonoscopy, make a referral to an endocrinologist and counsel an older patient on managing high blood pressure.

After 16 years as a nurse practitioner, Gray would love to open her own primary care practice. But she says a Pennsylvania law that requires nurse practitioners to have a contractual arrangement with a physician has kept nurses like her from striking out on their own.

“It’s a huge problem,” said Gray, who works for a hospital system in the Lehigh Valley. “There just aren’t enough physicians for all the people needing primary care.”

The influx of new patients into the health care system as a result of the Affordable Care Act is increasing demand for primary care providers, especially in underserved rural and urban areas. Studies by the Institute of Medicine and others have found that nurse practitioners—registered nurses with additional training and master’s or doctoral degrees—can help fill the gap. But laws like Pennsylvania’s make that difficult.

Legislative priorities

Changing state law to allow nurse practitioners to fully provide the clinical care they are skilled in—as they can in 21 states and the District of Columbia—is one of AARP Pennsylvania’s top legislative priorities for 2016.

State Sen. Pat Vance (R-Camp Hill), a former nurse who is championing a bill to revise the nurse practitioner law, regularly gets calls from constituents who cannot find a primary care doctor. If the law isn’t changed, she said, “there will be a lot of people with insurance and no one to take care of them.”

The current arrangement with physicians exists only on paper, said Gray, who lives in Bethlehem. “They might never step foot in your practice.”

A recent analysis estimated that Pennsylvania could gain more than 1,000 additional nurse practitioners if they were given full practice authority. And because treatment by nurse practitioners is generally less expensive than care by physicians, Pennsylvania would see savings of roughly $6.4 billion over a decade.

“This would just open up so much access to care,” Gray said. “For our profession to grow and meet the needs of our patients, this [legislation] is just critical.”

Many nurse practitioners live and work in rural or inner-city communities where it can be difficult to attract physicians, said Lorraine Bock, president of the Pennsylvania Coalition of Nurse Practitioners, which represents the state’s 9,500 nurse practitioners.

“The facts show that this is good for the patients, it’s good for the communities, and it’s good for the economy,” she said.

The Pennsylvania Medical Society, which represents doctors, opposes a change in the law and instead supports “team-based” care, in which nurse practitioners work on teams led by physicians, said Karen Rizzo, M.D., immediate past president of the society.

“I can’t imagine why our Legislature would want to fragment the care team and grant independent medical practice authority to any professional with less training than a physician,” Rizzo said. “Nor do all nurse practitioners, many of whom see physician collaboration as key to providing quality care statewide.”

In other areas, AARP wants a more even balance between funding for nursing homes and funding to support home- and community-based care for residents who want to stay in their homes, said Ray Landis, AARP Pennsylvania advocacy manager.

Currently, about three-fifths of the money goes to nursing homes.

“We’re in a much better position than where we were five years ago,” Landis said, “but we still need to improve significantly.”

AARP is also pushing for an update to Pennsylvania’s Older Adult Protective Services Act to address financial exploitation, which costs older adults billions of dollars nationwide every year.

A bill sponsored by state Rep. Tim Hennessey (R-North Coventry Township) would give local Area Agencies on Aging more power to investigate unscrupulous uses of power of attorney and increase the role of the financial services industry in tracking and reporting suspected fraud.

Hilary Appelman is a writer living in State College, Pa.